Talking Politics in the Seventeenth Century

22 September 2025In his new post, Professor Lloyd Bowen talks about his current research on political labels and words were used to confer identifies and divide people.

“Brexiteer”, ‘Remoaner”; “Fascist”, “Communist”; “Radical Left”, “Far Right”; “Snowflake”, “MAGA Nutjob”. Our modern politics has become a battleground of tribes and terms, labels and logos as much as of ideology and competing visions of a better future. Polarisation has produced a ready vocabulary of “us” and “them”, of ways of identifying “our kind of people” and “those kinds of people”.

Although these terms are a product of modern political divisions, pejorative political labelling is not. My current research project investigates some of the roots of this process by examining a critical time of political polarisation, but also of inventive name-making: the seventeenth century.

The seventeenth century saw one of the most consequential political conflicts of the early modern world: the British civil wars (c.1637-c.1651), a period which witnessed devastating armed conflict between parliamentarians and royalists, but also deep ideological division between communities throughout Britain and Ireland. Importantly, these convulsions also saw an outpouring of vitriol and a kind of political identity formation which was profoundly shaped by labels and language. These conflicts gave us “Cavaliers” and “Roundheads”, stereotypes which could be used to label and identify opponents, but they also produced other political labels for interest groups at the time, including “Levellers”, “Independents”, “Commonwealthsmen”, “Courtiers” and “Royalists”.

Source: A Dialogue, or Rather a Parley Between Prince Ruperts Dogge Whose Name is Puddle, and Tobies Dog Whose Name is Pepper, 1643

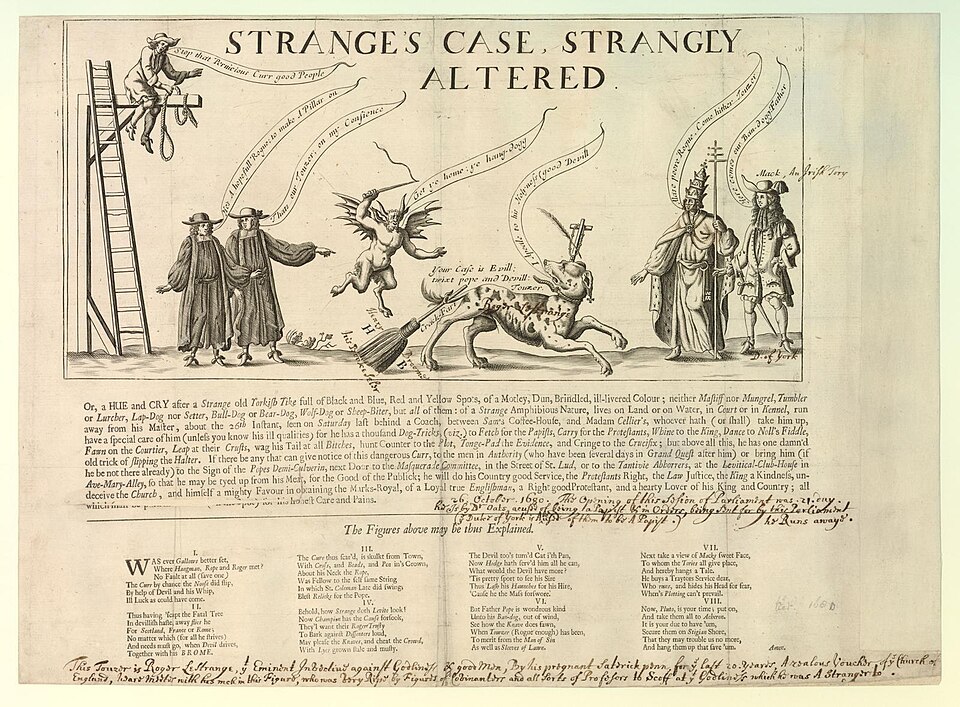

The civil wars had a profound legacy of political and religious division, and the later seventeenth century witnessed efforts to exclude the legitimate heir from acceding to the throne; plots and assassination attempts; and a foreign invasion and ejection of the monarch in the so-called “Glorious Revolution” of 1688-89. These episodes also produced a wealth of new terms for one’s political opponents including “Yorkist”, “Tantivy”, and the most enduring labels, “Whig” and “Tory”, which were popularised in the 1670s. There was also a resurgence in older forms of abuse, particularly calling one’s enemies “Papists” (which is to say, “Catholics”) or “Fanatics” (which is to say, Protestant nonconformists).

This year I received a grant from the British Academy and the Leverhulme Trust to support research into the ways in which these ‘new coyn’d words’ helped divide communities in the seventeenth century, and to examine how they contributed to a kind of new popular associational politics. Over the summer I have been working in several archives trying to find traces of how people understood the dynamics of this new politics and of how their language and labelling practices allowed them to express their political loyalties and develop new political identities.

One lesson from this kind of research is that you can come up against comparative dead-ends as well as the illuminating manuscript. I had thought to explore legal archives to trace individuals bringing cases of slander and sedition involving these terms. However, as I have discovered, this was much less common in some periods than others, and it was also the case that these words were not necessarily actionable: you might be prosecuted if you called someone a “Roundheaded dog” during the republican era of the 1650s; however, identifying a man as a “Tory dunce” was not necessarily sufficient to support a legal case in the 1680s (although impugning a woman’s reputation – by calling her a “poxy Whiggish whore” – was sufficient to bring you before a church court).

Source: Strange’s Case, Strangly Altered, 1680, Print

To try and get round these silences, I have been examining more anecdotal and impressionistic sources such as diaries and correspondence in addition to legal materials. Through these I have found a fascinating landscape of early modern people encountering a new, and at times disorienting, soundscape of political labels.

One aspect of my research is to try and explore how these labels crossed geographical, and sometimes linguistic boundaries. It is important to note in this context, for example, that “Whig” was originally a Scottish term anchored in religious discourse, while ‘Tory’, or “Toraidh”, was a Gaelic word applied initially to Irish bandits. The new political labels crossed the linguistic divide in Wales as loanwords (that is, borrowed directly from the English) where we encounter “Cafelîr” (“Cavalier”), “Rowndiad” (“Roundheads”); “ffanatic” (“fanatic”); and “Tori” (Tory).

But these labels were not confined to Britain and Ireland: they also helped inform the political foundations of the nascent empire. In 1649, for example, Maryland in the American colonies passed an act designed to prevent conflicts among its population by disallowing the use of terms including ‘Roundhead’. In Monserrat, a British territory in the Caribbean, meanwhile, the local assembly in the 1680s was concerned about drunken colonists calling one another “English dogg, Scots dogg, Tory, Irish dogg, Cavalier and Roundheade”. Over the coming year, I will explore further how Britain’s early colonies inherited the partisan languages of the metropole, and how these terms helped shape emerging imperial politics.

This work with manuscripts in the archives will be complemented by research in the enormous volume of topical printed works which accompanied these political crises in the seventeenth century (and which my class studies on my Final Year module on early modern print culture at Cardiff). Regular newspapers and a vibrant world of polemic and pamphleteering ensured that there was a popularisation of these kinds of political labels. However, there was also a fertile interplay between popular speech and the printed text – if you wanted to sell copy you needed to ensure you were reflecting contemporary language as well as helping shape its future deployment.

This research is in its early stages, but it has been fascinating getting to grips with this slippery topic of early modern political speech and political labelling. So, the next time you encounter a writer or speaker labelling an individual or group with whom they disagree, be alive to the terms they use, and try to reflect on the deep history of this kind of activity.

- American history

- Central and East European

- Current Projects

- Digital History

- Early modern history

- East Asian History

- Enlightenment

- Enviromental history

- European history

- Events

- History@Cardiff Blog

- Intellectual History

- Medieval history

- Middle East

- Modern history

- New publications

- News

- North Africa

- Politics and diplomacy

- Research Ethics

- Russian History

- Seminar

- Social history of medicine

- Teaching

- The Crusades

- Uncategorised

- Welsh History

- Pétain’s Silence

- Talking Politics in the Seventeenth Century

- Reflections on POWs on the 80th anniversary of the Second World War – views from a dissertation student

- The Long Life of Dic Siôn Dafydd and his ‘children’

- Collaboration across the pond: uniting histories of religious toleration in the American Revolution and European Enlightenment