Taking The Long View: Muslims, Political Protest, and The European Public Sphere

8 August 2024in his post, Gavin Murray-Miller draws on work for his forthcoming book on Muslim Europe to explore the longer history of Muslim public activism in Europe and the crucial role Muslim activists have played.

In the run-up to the French election held in July 2024, the city of Lyon momentarily offered an image characteristic of the growing political divisions running through the country. In the middle of the afternoon, a throng of thirty masked men descended into the old medieval quarter chanting “Islam out of Europe!” While the right-wing demonstration in Lyon was theatrical, the message it conveyed has been reiterated across European nations over the past two decades. Anti-Muslim sentiment is now common currency among Europe’s resurgent right-wing, provoking reactions from small bands of militants to national leaders like Viktor Orbán, who once warned European capitals were in danger of becoming a “Muslim majority.” Such pronouncements have increasingly crept into the political centre, driven by fears of terrorism and the swelling number of asylum seekers heading to the continent. A poll conducted by the anti-fascist group Hope not Hate in 2018 found that a third of Britons saw Islam as a threat to their way of life and values. The recent wave of protests surrounding the ongoing Israeli-Palestinian conflict has heightened these tensions. Earlier this year, as pro-Palestinian rallies seized London, member of the Conservative Party expressed alarm over the ostensibly anti-Semitic and “pro-Islamist” message espoused by organizers. MP Lee Anderson went as far as to accuse London’s Muslim mayor, Sadiq Khan, of being controlled by “Islamists” after he failed to rein in the protest marches. At the same time, a rally organized in Hamburg, Germany in which some participants called for the restoration of a caliphate elicited a response from Interior Minister, Nancy Faeser, who pledged to combat anti-Semitism and “terror propaganda” disseminated by extremist groups. “If you want a caliphate,” she replied to protestors, “you’ve come to the wrong place in Germany.”

What might at first seem a response to present-day political currents roiling European society is, in many ways, an old story. The notion that Islam is alien to European society and culture is hardly new. It can be traced back to the formative years of the Islamic faith when the medieval kingdoms of continental Europe warned of the impending submission of Christendom to Islam. Yet if “Islamophobia” has deep roots in Europe’s history, the current tenor of this rhetoric is distinctive. It has found expression in contemporary issues ranging from concerns over immigration and European identity to the threat posed by terrorism and “Islamic fundamentalism.” In essence, Islam today is a political rather than theological concern. Questions regarding Islam’s place in Europe touch upon controversial claims regarding the presence of “foreigners” in host countries, the racial identity and composition of European societies, and the meaning of inclusion and secularism in Western democracies.

Often what the media fails to acknowledge, though, is that the presence of Muslims in the European political and public sphere is hardly novel and extends back much further than traditionally assumed. In the late nineteenth century, a range of Muslim social and political organizations existed across Europe. In Liverpool and London, small Muslim communities led by William Abdullah Quilliam and the Indian-born jurist Kwaja Kamal-ud-Din played an instrumental role in building political platforms that aimed to speak for Muslim public opinion in the United Kingdom. Victorian activists ran newspapers and formed advocacy groups with names like the British Muslim Society and the Islamic Society. Their efforts paved the way for present-day national organizations such as The Muslim Council of Britain by foregrounding issues related to mosque building, education, the maintenance of Muslim burial grounds, and even foreign relations with Muslim states. Quilliam was never reticent on his imagined role as “leader of the English Mussulmans,” and he and his allies worked diligently to establish a public Muslim voice in the country by currying favour with influential political elites, even managing to convert some in the process.

Image: William Abdullah Quilliam, the representative of Islam in Britain and founder of the Liverpool Muslim Institute.

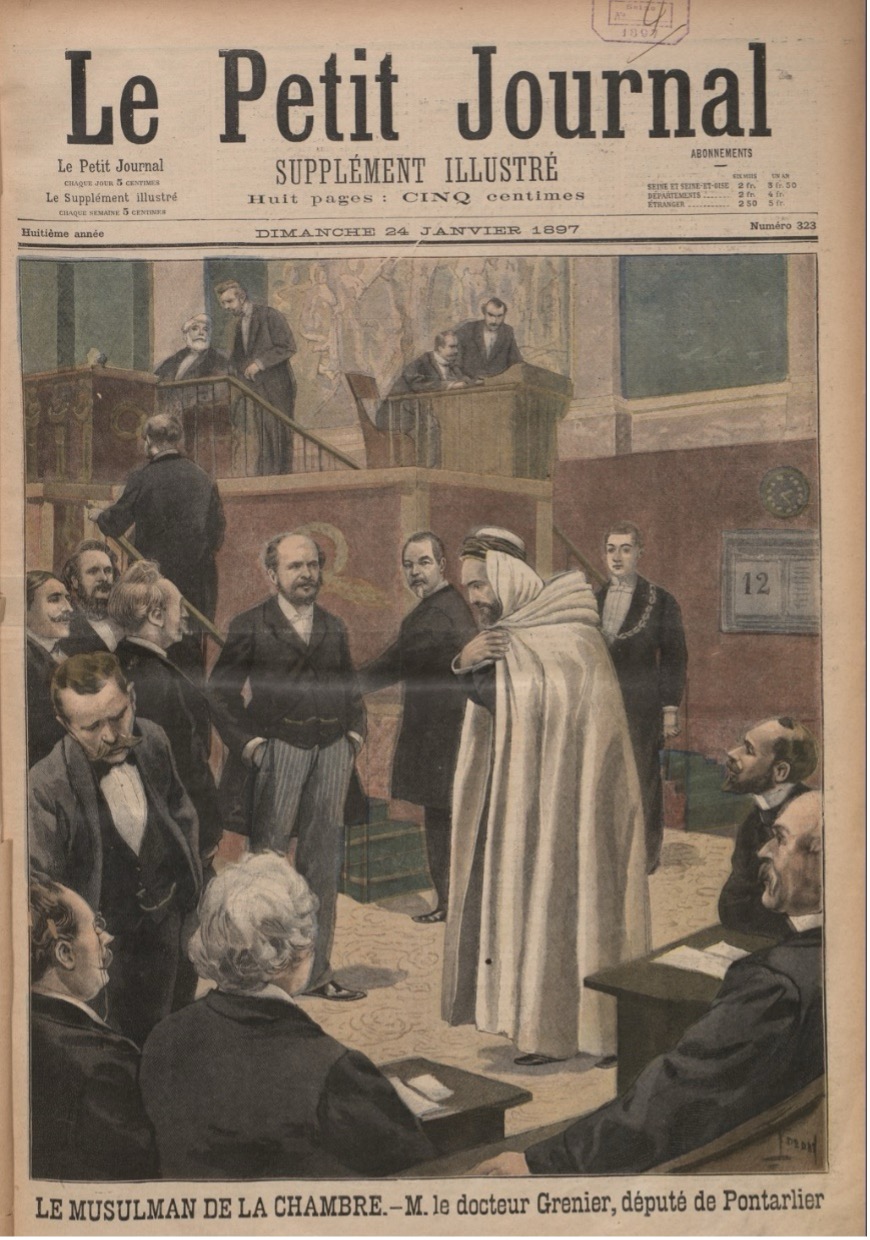

In France, the picture was similar. French colonial expansion into North Africa during the nineteenth century encouraged a new interest in the Muslim world among sections of elite society. “Mohammedanism has become a current question [and] is very much in favor among us,” admitted the writer Henry de Castries in the early 1890s. Taking stock of their empire, certain French imperialists were inclined to see their country as a “Muslim power” analogous to the Ottoman and Mughal dynasties. “We are . . . a Muslim nation,” claimed the philosopher Pierre Laffitte in 1882 when considering the millions of Muslims France ruled over. These musings were not simply imperialist fantasies. In 1896, Philippe Grenier, an obscure doctor and Muslim convert from the sleepy commune of Pontarlier, won a seat in the National Assembly, making him the first elected Muslim representative in France. Islam constituted a centerpiece of his election campaign, and Grenier himself became notorious for wearing the North African burnous in parliament. During his brief political career, Grenier was determined to use his new-found political position to speak out on behalf of French Muslims and even promote a brand of “French Islam.” His momentary celebrity—all but forgotten today—spurred others into action. At the turn of the century, a coterie of North Africans and Turkish exiles living in the French capital began running newspapers and organizing, labeling themselves the “Muslim colony of Paris.”

Image: Philippe Grenier entering the National Assembly. Le Petit Journal, 24 January 1897. Gallica/Bibliothèque Nationale de France

It wasn’t simply that Muslims were organizing politically by the late nineteenth century. It was their tactics that were revealing. Muslim men and women tied their confessional identity to a host of international humanitarian and social issues, linking their cause for public recognition with broader calls for social justice and peace. Muslims took to the press to decry Britain’s wars in Afghanistan, protested when the Entente Powers (France, Russia, and Britain) went to war against the Ottoman Empire in 1914, and readily spoke out against the mistreatment of colonial subjects in European empires overseas. Publicists also tackled the thorny subject of gender equality, with some speakers drawing comparisons between the teachings of the Qur’an and the growing cause of female emancipation by the end of the 1800s. The activist Dusé Mohamed Ali was particularly noteworthy. An Egyptian by birth who came to England in the 1890s, Dusé made a name for himself as an author and anticolonial activist. From his office on Fleet Street, he edited the newspaper The African Times, which claimed to speak for all the subjugated peoples of the earth. As Dusé once boasted, his editorial office was akin to a “clearing house for African and Oriental grievances.” His prolific writing was matched by an energetic commitment to reform. In addition to working through London’s Muslim networks to effect change, he helped organize the Universal Races Congress in 1911, an international event that brought together leading intellectuals and reformers dedicated to human rights and racial justice. Dusé’s political attachments were far-reaching, showing the extent of Muslim political activism in the years before the First World War.

Image: Dusé Mohamed Ali, Muslim activist and anti-colonial campaigner.

As I discuss in my forthcoming book Muslim Europe, these details are part and parcel of a longer history that continues to play out in the European public sphere to this day. Muslim public activism and protest have been a consistent feature of European political life for over a century. Muslims, whether of foreign extract or European “born and bred” (to use Quilliam’s expression), have regularly felt obliged to speak out on issues sensitive to the global Muslim community, often weighing in on foreign policy topics and expressing solidarity with demands for global justice as a minority group. For conservatives prone to consider Islam as a “problem” in need of solving or who question whether Islam can be harmonized with a liberal, secular culture, the longue durée of Muslim politics in Europe can be informative. Much like previous generations, foreign-born and European activists today persist in building coalitions and taking to the press in search of greater social recognition. They appeal to notions of diversity, civil rights, and global justice. Politics are typically a short-term game predicated upon election cycles and momentary concerns. History, by contrast, focuses on long-term developments and continuities. Taking the long view, a different picture emerges. Whether conservatives like it or not, Muslim politics are European politics.

Gavin Murray-Miller is a Reader in Modern History at Cardiff. His latest book Muslim Europe: How Religion and Empire Transformed European Society will be appearing in early 2025.

- American history

- Central and East European

- Current Projects

- Digital History

- Early modern history

- East Asian History

- Enlightenment

- Enviromental history

- European history

- Events

- History@Cardiff Blog

- Intellectual History

- Medieval history

- Middle East

- Modern history

- New publications

- News

- North Africa

- Politics and diplomacy

- Research Ethics

- Russian History

- Seminar

- Social history of medicine

- Teaching

- The Crusades

- Uncategorised

- Welsh History

- Pétain’s Silence

- Talking Politics in the Seventeenth Century

- Reflections on POWs on the 80th anniversary of the Second World War – views from a dissertation student

- The Long Life of Dic Siôn Dafydd and his ‘children’

- Collaboration across the pond: uniting histories of religious toleration in the American Revolution and European Enlightenment