Living with Seasons

11 June 2024In this multi-authored post, a series of scholars from Cardiff explore the idea of living with seasons from different perspectives

It is the time of year when trees are in bloom and Cathays is taking part in the springtime show. But the daffodils came up a month earlier than they did last year, and the wet weather is extending the hungry gap longer. As the seasons change around us, it is urgent that we explore the ways in which seasons shaped and continue to shape aspects of everyday life: first up, rivers and the environment. As historians, our methods have to attend to sources and their limitations so that we are prepared to say how we know what we know about seasonality. In the early American south, colonizers consistently failed to witness (and thus understand) Indigenous women’s agriculture. They were not privy to women’s activities gathering wild water plants above riverine fall lines, which Europeans’ watercrafts were incapable of fording or portaging. Only with the help of archaeological records and by cross-referencing travel, naturalist, and ethnobotanical accounts produced by writers working for different imperial powers has it been possible to better understand and describe this seasonal labour in zones that experienced seasonal migration as well as intense seasonal floods. Yet Anglo-Europeans who lacked this understanding at the time repeatedly used rivers as boundaries in treaties with each other. Thinking about the absence of seasonal, riverine knowledge in the early American south raised questions about how Indigenous knowledge and experiences of seasons were used to challenge borders and impose boundaries. It suggests how we not only need to think about different forms of knowledge and the nature of Indigenous knowledge, but also about gendering of knowledge about seasons and everyday practices.

![Alonso de Santa Cruz and Archivo General De Indias, Mapa del Golfo y costa de la Nueva España: desde el Río de Panuco hasta el cabo de Santa Elena. [?, 1572] Map. Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2003623374/. This map, commonly referred to as the “Soto map” was drawn using knowledge from captured Indigenous informers and the Spaniards who went on the expedition of Hernando de Soto. It shows the rivers that Spanish colonists learned about and failed to access. The map fails to accurately depict the overland route of the expedition. AltText: This is a map showing the Gulf of Mexico from present-day Texas to Florida. The whole bottom half, meant to depict the ocean, is blank. From the ocean into the continent run many rivers, which are marked with an icon meant to represent Native American towns.](http://blogs.cardiff.ac.uk/history-at-cardiff/wp-content/uploads/sites/632/2024/05/Map.png)

Seasons are often thought of differently across the globe; while in north-west Europe we define seasons based on temperature, many parts of the world, especially those around the equator, will define seasons based on rainfall, with marked wet and dry seasons throughout the year. In regions where rainfall is the main source of water for agriculture and domestic water use, the wet season is of significant importance. Crops are grown during the wet season, and harvested at the end of the season, and water is collected for use throughout the dry season. Ploughing, planting, and harvesting are all closely tied to the seasonal cycle of rainfall. Workers may migrate to urban areas to find work during the dry season, returning to rural areas for the onset of the rains. Changes and variations in the wet and dry seasons thus have significant societal impacts, and if not properly planned for, may lead to food shortages. In some tropical regions we are starting to see increasingly hot temperatures prior to the onset of the rains (including recent heatwaves in India). This creates a range of challenges, especially for perennial crops, and in regions where hydropower is an important energy source.

Are there seasons in memory? Can we conceptualize memory studies within a paradigm of seasons and seasonality? Much of the work on memory cultures is conceived of in terms of spatial linearity, often centred on notions of generational transmission – from the early ground-breaking work in the 1930s of philosopher Maurice Halbwachs on social structures and collective memory to the work of historians, such as Jenny Wüstenberg and Aline Sierp, using social network theory to chart the transnational exchanges of memory narratives in the contemporary era. But what if we looked beyond lines towards seasonality and notions of memory patterning that might work better with fluvial metaphors – dry seasons (where memory work is latent, germinating, but not yet emerging into public consciousness) and wet seasons (where there may be a deluge of memory work that risks breaching often well-established defences in the collective zeitgeist). Seasonality as an intellectual paradigm could also help us think differently about the work of memory globally. Do we work to the same seasonal rhythm of remembrance across nations, regions, communities?

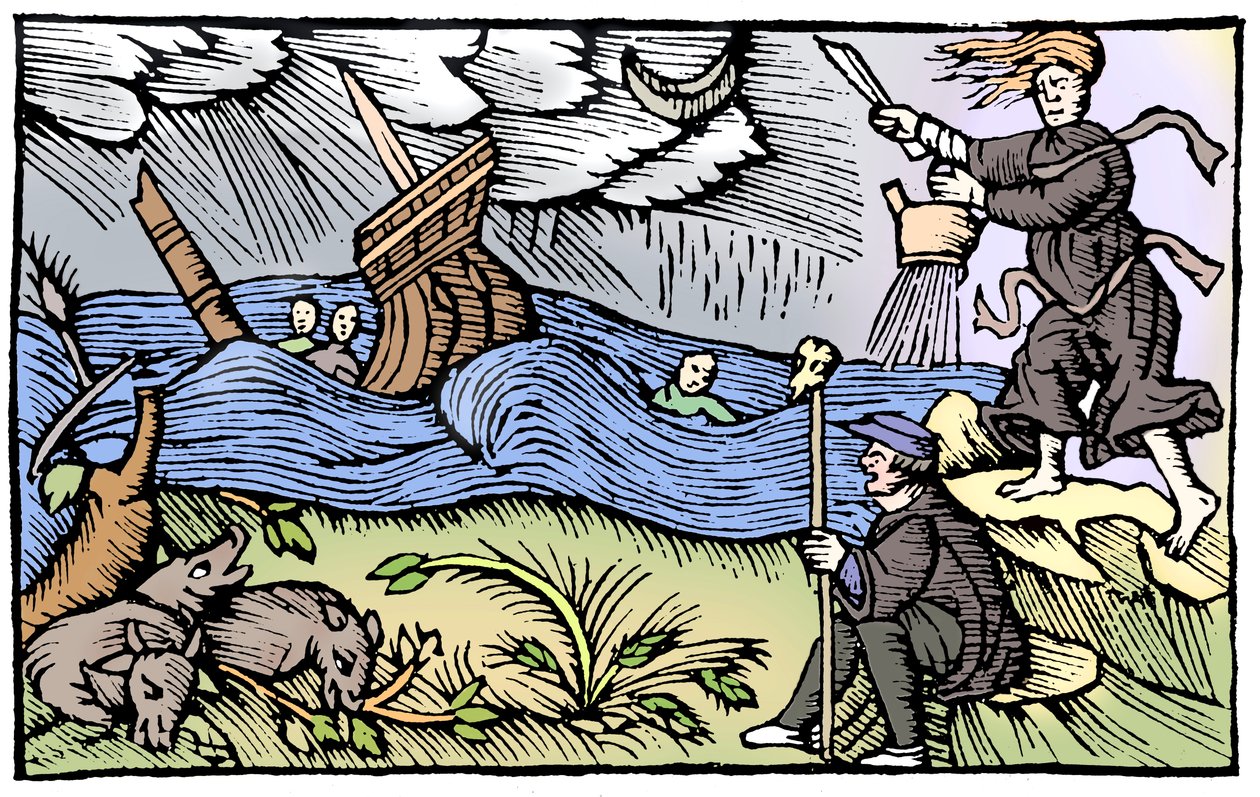

Memory played a central role in how people in the past thought about seasonality and the weather. When faced with seemingly ‘unseasonal’ weather shocks – from thunderstorms and floods to heat waves and droughts – they turned to the past in an attempt to understand their significance. When a devastating thunderstorm hit central Europe in August 1562, damaging buildings, killing livestock, and destroying crops, people recalled that no one could remember a similar event or such a poor summer over the last hundred years. The thunderstorm and other weather events of that year were viewed as ‘unnatural’ as people drew on their memory of previous summers in an attempt to make sense of the disruption to the normal ebb and flow of the seasons in 1562. We can see this connection between seasonality, disruption and memory in other examples. For instance, one rainfall observer at Ross on the English-Welsh border in his report on spring in 1893, explained how ‘no similar season has occurred since 1870’ as he tried to understand the severity of drought that year. Newspapers used words such as ‘unparalleled’ and ‘exceptional’ to describe the impact of weather shocks on the seasons. Memories of hot summers, low rainfall, severe storms, snowfall or other adverse weather served as an important tool in nineteenth-century newspaper reporting to understand how the seasons were being affected and the consequences for communities, particularly for those communities which were more vulnerable to seasonal fluctuations.

Seasons are also times of movement, and of knowing (how to move, and what to do with the season). In the central-east African forests and grasslands around the Nile’s Sudd, the largest swamp in the world, seasons create pathways of generations of humans and animals in travels that rework landscapes. These seasonal paths and plans are celebrated through song-stories and names, celebrating genealogies of negotiation (of other people, and of seasonal terrains). Agro-pastoralist Dinka ‘bull songs’ trace both families and cattle across seasons and space since maybe the 1500s, through wet season sorghum fields and dry season grasslands. These songs emphasise how the world has been spoiled before, and rebuilt; they also document the knowledge that is needed to navigate these seasons and their safe spaces. Rainy seasons allow escape and safe isolation: for roughly four or five months, some islands of the Sudd marshes remain inaccessible to both the Turkiyya slave-raider and the UN helicopter. Even in dry seasons, they are navigable only via knowledge of the changing marshes and Nile weeds over decades of flood and retreat. These protective seasons are why what is now South Sudan was only incorporated into colonial markets in the 1900s, once the Sudd was physically cut through by British agents. Villages fortified against the slave raiders of the 1850s still left their riverfronts open. With this came new seasons of labour migrations: men seeking the cash for a bicycle from Uganda before returning for harvest work, and women’s inverse seasons of seeding and weeding, and their experimental knowledge of seed developments for changing soils and rain patterns. Not messing with seasonal systems, not making-static, is a core political issue here: for example, the recurrent proposal of the Jonglei Canal scheme to drain the Sudd for static irrigated mass farms has created uprisings in the 1940s, the 1970s, and two years ago; and the Sudan war now risks jeopardising many families’ safety by stopping seasonal migration for cash work in factories, and allowing scrub to overgrow cleared seasonal farms and water caches.

Why think of different seasons when trade in agri-food products enables us to buy fruits and vegetables from all over the world all year round? It is now common to go to the supermarkets to find French beans from Kenya or tomatoes from Morocco. Consequences of international trade are increasing our dependence on imports from countries which often prefer to export to us than sell to their own population as the financial benefits are greater – putting the local population at risk of food insecurity. With an expanding amount of foreign land used to grow food which we want to enjoy every day of the year, extra pressures are placed on the local infrastructures and natural resources. The poor quality of the soil, restricted access to water and increased agricultural pollution are impacting foreign countries due to our Western lifestyle of wanting tomatoes in winter. Such an approach to food means that even UK/Welsh producers when selling their produce via fruit and veg boxes or farmers markets supplement their meagre products in winter with foreign products thereby impacting climate change and biodiversity challenges abroad because they do not want to lose customers. Living with seasons means eating with the seasons and asking ourselves whether we need foods from all around the world all of the time – foods that have huge ramifications for the local population and for the environment.

Seasons are, therefore, simultaneously the most local and global of lenses through which we can understand the human experience. As these contributions have illustrated, ‘Living with Seasons’ has prompted phenomenal ingenuity and creativity from humanity, but also dire and desperate violence. In every region of the globe, seasonal change and the temporal rhythms it creates has established the patterns of human existence: from agrarian and commercial life to the deeper memories of environmental trauma and the movement of people. Because no part of the earth is untouched by the seasons, no human society – past, present, or future – can be fully understood without thinking about these changes. As these patterns inevitably (and unavoidably) change with climate collapse in the coming decades, we must draw from this deep well of experience to comprehend new adaptations, methods for survival, and seasonal rhythms that will be dramatically unfamiliar.

Contributors: Rachel Herrmann, Keir Waddington, Mark Williams, Caroline Wainwright, Claire Gorrara, Nicki Kindersley, Ludivine Petetin

References

Rountree, Helen C. ‘Powhatan Indian Women: The People Captain John Smith Barely Saw’. Ethnohistory, 45:1 (1998), pp. 1–29.

Ethridge, Robbie. Creek country: the Creek Indians and their world (Chapel Hill, NC, 2003), ch. 3.

Halbwachs, Maurice. Les Cadres sociaux de la mémoire (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1952).

Wüstenberg, Jenny and Aline Sierp, Agency in Transnational Memory Politics (Berghahn 2020).

Mading Deng, Francis. The Dinka and their songs (Oxford, 1973).

Johnson, Douglas H. South Sudan: A New History for a New Nation (Ohio, 2016). Chapter 3, ‘Trees and wandering bulls.’

- American history

- Central and East European

- Current Projects

- Digital History

- Early modern history

- East Asian History

- Enlightenment

- Enviromental history

- European history

- Events

- History@Cardiff Blog

- Intellectual History

- Medieval history

- Middle East

- Modern history

- New publications

- News

- North Africa

- Politics and diplomacy

- Research Ethics

- Russian History

- Seminar

- Social history of medicine

- Teaching

- The Crusades

- Uncategorised

- Welsh History

- Pétain’s Silence

- Talking Politics in the Seventeenth Century

- Reflections on POWs on the 80th anniversary of the Second World War – views from a dissertation student

- The Long Life of Dic Siôn Dafydd and his ‘children’

- Collaboration across the pond: uniting histories of religious toleration in the American Revolution and European Enlightenment