X-Rays Galore: Blackfriary Metal Finds

3 January 2020Following excavations from 2010-2018, the Blackfriary metal finds travelled from Trim, Ireland to Cardiff University in January 2019 for conservation. I was assigned the objects at the beginning of this term and was tasked with their preliminary understanding. I will eventually devise a treatment plan for these objects. For those that do not know much about the Blackfriary site, have a look here: http://bafs.ie/.

I received three boxes containing over 800 objects on my first day of class in September. The finds consist mostly of iron and copper alloy objects, but there are some outliers such as silver and lead as well. The first, and only, step to fully understand these finds is to x-ray them to see details the corrosion may be obscuring. Luckily, most of the iron is not so badly corroded that they are unidentifiable—spoiler alert, there are a lot of nails!

Since the Blackfriary dig is overseen by the National Museum of Ireland (NMI), the processing of these objects must adhere to the NMI standards, which includes x-raying all the metal finds. For more information on the practice of x-radiography at Cardiff University see here: https://blogs.cardiff.ac.uk/conservation/2016/11/23/looking-beneath-the-layers/. I x-rayed the following objects at 90 KV for two to three minutes because metal requires higher KV to penetrate the material.

Below, are photographs of five objects in their current condition along with their x-rays. Details of the objects and x-radiography results will be discussed, but treatments will not, as I have just begun to understand these finds. Each object is labelled with its context and item number, as well as the description Blackfriary provided.

919:15: Irregular shaped piece of worked lead.

I knew x-raying a lead object would not provide more information about the object itself, but I still x-rayed it to confirm it is lead and to adhere to the NMI standards. Lead is a very dense metal and the x-rays cannot penetrate it, which is why the find shows up fully white (it’s good to know the lead protection we wear when getting x-rays at the doctor/dentist actually works!). Small areas of white, powdery lead corrosion can be seen in the photos (Canadian Conservation Institute).

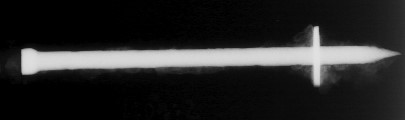

1109:2: Large straight globular nail

This nail shows the typical corrosion that is on most of the iron objects—a lumpy orangish corrosion product with brown soil adhered to it. At first, I thought the bulbous mass around the point was all corrosion, but after x-raying I could clearly see there is a metal component that encircles the shaft of the nail. The x-rays penetrate through the corrosion and the faint outline of the corrosion is visible on the x-ray film.

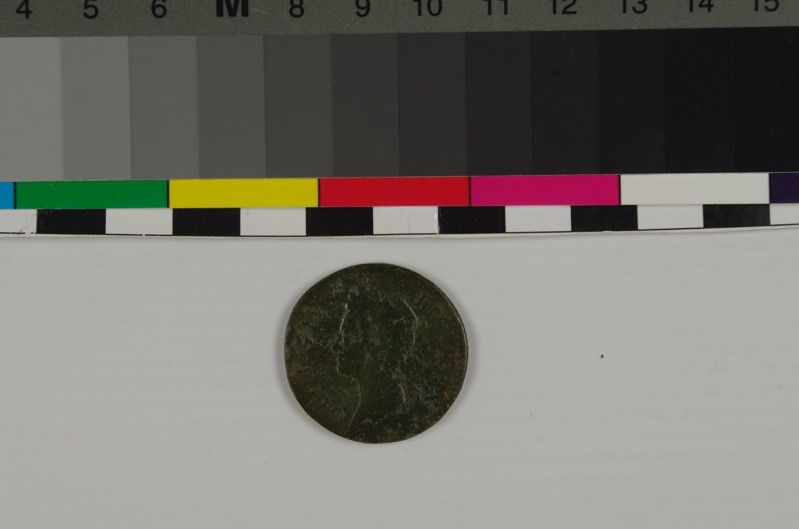

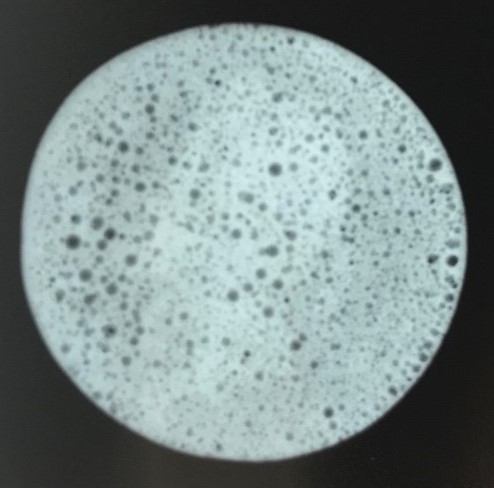

703:153: Coin from George the second.

Blackfriary identified this as a coin from the reign of George II (1727-1760). “GEORGIUS II REX” can be seen on the face of the coin, while “HIBERNIA” can be made out on the reverse. This coin is made of copper or a copper alloy, since it has oxidized to a distinctive green color. This corrosion is relatively stable and known as a patina layer. I was quite surprised to see the x-ray since the coin appears in decent condition, but the x-ray shows a porous looking structure. My initial thought as to why this could be is that the copper is preferentially corroding to whatever metal it has been alloyed with, which is leaving behind a porous structure. I will have to research more to be certain why this coin appears this way.

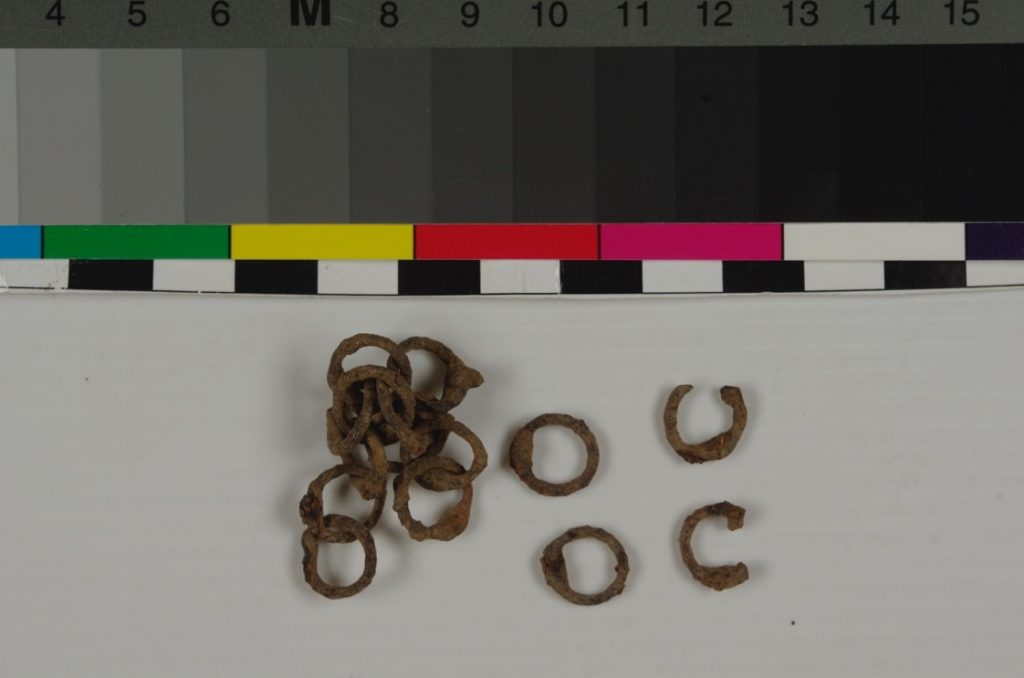

624:19: Small chain-linked metal fragments. Count of rings 4 loose rings and 11 connected rings.

An exciting find was this piece of iron mail—or maille—which I believe is wedge-riveted mail. The rivets are the thicker portion of the rings. Archaeological iron mail can often corrode into a solid chunk where only the outlines of some rings can be seen, so this relatively flexible fragment is a rare find (Wijnhoven 2015). This piece is so disjointed that I cannot discern what its original function may have been. It could have been part of a hood, mantle, or coat, but with only 15 rings, I cannot tell (Wijnhoven 2015). Perhaps someone more experienced in mail design and use could conclude more from this piece, but I will have to research quite a bit more to fully understand this interesting find.

1002:29: Arc-shaped fragment; thin, convex groove equidistant from rim. Black colour.

This find was categorized as ceramic, but upon handling, I was not sure that was the case. My lecturer, Phil Parkes, thought it may be pewter and to x-ray it to see what that may reveal. From the x-ray (90 KV, 3 min), I can tell it is not ceramic, but metal and possibly pewter. This fragment is only 0.27 cm thick but shows as a dense material in the x-ray. Historically, pewter was an alloy made of a majority of tin and usually contained small amounts of copper, antimony, or bismuth, and sometimes lead, which could be why the x-ray shows this thin fragment as so dense (The Pewter Society).

365 objects have been x-rayed so far, which is just under half of the finds. Once all the objects have been x-rayed, I will determine which finds should be treated—in consultation with the Blackfriary staff—and devise a treatment plan. Be on the lookout for another post about more x-radiography results or a treatment plan!

All photographs and x-rays by Alice Blakely.

References

Canadian Conservation Institute. 2019. Lead in Museum Collections and Heritage Buildings. Available at: https://www.canada.ca/en/conservation-institute/services/conservation-preservation-publications/canadian-conservation-institute-notes/lead-museum-collections.html. [Accessed: 17 December 2019].

The Pewter Society. Available at: https://www.pewtersociety.org/. [Accessed: 17 December 2019].

Wijnhoven, M. 2015. Filling in the Gaps: Conservation and Reconstruction of Archaeological Mail Armour. Journal of Conservation and Museum Studies, 13(1). DOI: http://doi.org/10.5334/jcms.1021226.

- March 2024 (1)

- December 2023 (1)

- November 2023 (2)

- March 2023 (2)

- January 2023 (6)

- November 2022 (1)

- October 2022 (1)

- June 2022 (6)

- January 2022 (8)

- March 2021 (2)

- January 2021 (3)

- June 2020 (1)

- May 2020 (1)

- April 2020 (1)

- March 2020 (4)

- February 2020 (3)

- January 2020 (5)

- November 2019 (1)

- October 2019 (1)

- June 2019 (1)

- April 2019 (2)

- March 2019 (1)

- January 2019 (1)

- August 2018 (2)

- July 2018 (5)

- June 2018 (2)

- May 2018 (3)

- March 2018 (1)

- February 2018 (3)

- January 2018 (1)

- December 2017 (1)

- October 2017 (4)

- September 2017 (1)

- August 2017 (2)

- July 2017 (1)

- June 2017 (3)

- May 2017 (1)

- March 2017 (2)

- February 2017 (1)

- January 2017 (5)

- December 2016 (2)

- November 2016 (2)

- June 2016 (1)

- March 2016 (1)

- December 2015 (1)

- July 2014 (1)

- February 2014 (1)

- January 2014 (4)