The End of a Journey: Analysis of the Black Friary Glass

3 January 2018

Following the completion of the physical treatment of the Black Friary stained glass, all thoughts turned to the study and analysis of selected pieces from the collection. I selected a range of pieces to begin to characterize the elemental composition of the glass as well as the designs on the surface. With the help of our lab supervisor and senior conservator Phil Parkes, the selected pieces were analyzed using a scanning electron microscope (SEM). Over the course of several hours, we looked at six different glass fragments. Because of the nature of glass decay, wherein certain elements (usually Potassium in medieval glass) are lost from within the silica matrix, multiple areas on each glass sample were tested to create an overall characterization of each piece. The results for all the pieces tested fell within the normal range for medieval European glass with a main structure made of between 60% to 70% silica with a potassium flux and various trace elements. The blue glass tested had high levels of cobalt and copper while the aqua blue color found in one of the pieces was caused by a mix of manganese and iron. The most common decorations seen on the glass we treated were made of a red-brown enamel that derived its hue from oxidized iron.

One of the advantages of using the SEM is being able to not only look at the composition of the glass but to take pictures of the surface! The pictures taken with an SEM are created by the reflection or absorption of electrons as they bounce off the surface of the object. Darker areas are caused by the electrons passing through that space while brighter areas are denser and bounce back electrons to the sensor.

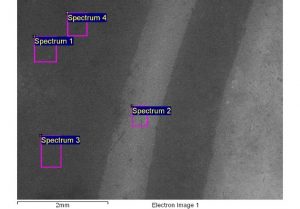

A conserved piece of glass with a red enamel design that was analysed using the SEM, and the resulting image of the surface.

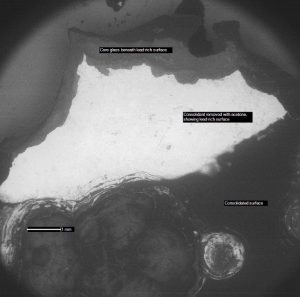

This can be seen quite clearly in this image taken of a piece of glass with a red design. The high amounts of iron (a denser element) in the design cause it to appear light grey in the image. Each square shows where we analyzed this piece for compositional data. While inspecting a piece of bright blue glass, we found something rather interesting. The surface of the glass appeared a bright white while being photographed during analysis. Further investigation revealed that the surface was composed of around 40% lead while the broken edges where the core glass was exposed only had trace amounts. We speculate that this could be due to a lead wash on the glass during manufacture or to the lead cames that held the glass in place within the window depositing lead into the decomposing glass surface over many years.

The blue piece of glass after conservation and the corresponding SEM image. The white area on the glass surface is caused by high levels of lead that are otherwise not visible to the naked eye.

After working on this project for two years, I was sad to see it end but delighted to be able to send the glass back to its home in Ireland. I was also overwhelmed by the generosity of the staff at the Black Friary site who offered me the opportunity to work on the site for two weeks during the summer of 2017 with their archaeology students! Having never worked on an active archaeology site, it was a wonderful opportunity to talk with the archaeologists and learn more about the site and the artifacts being recovered. While there, I was taught the basics of being an archaeologist, from troweling techniques to taking levels and drawing site plans. I also helped to continue the excavation, documentation, and packaging of even more stained glass. We were lucky enough to find a colored piece that was still transparent and had a visible design! I loved every minute of it and I hope to visit again in the future to see what they have uncovered and learned!

Archaeology students excavating glass on the Black Friary site. A wonderfully preserved piece of stained glass found during the summer excavation.

Many thanks again to all the students who worked on the project, Jane Henderson and Phil Parkes for supervision in the lab, and everyone at the Black Friary for your support through this entire endeavor.

If you missed the previous installments of the Black Friary glass story, check out Part 1 and Part 2. For more about the excavations, check out this blog by the Irish Archaeology Field School (IAFS), which found the glass.

- March 2024 (1)

- December 2023 (1)

- November 2023 (2)

- March 2023 (2)

- January 2023 (6)

- November 2022 (1)

- October 2022 (1)

- June 2022 (6)

- January 2022 (8)

- March 2021 (2)

- January 2021 (3)

- June 2020 (1)

- May 2020 (1)

- April 2020 (1)

- March 2020 (4)

- February 2020 (3)

- January 2020 (5)

- November 2019 (1)

- October 2019 (1)

- June 2019 (1)

- April 2019 (2)

- March 2019 (1)

- January 2019 (1)

- August 2018 (2)

- July 2018 (5)

- June 2018 (2)

- May 2018 (3)

- March 2018 (1)

- February 2018 (3)

- January 2018 (1)

- December 2017 (1)

- October 2017 (4)

- September 2017 (1)

- August 2017 (2)

- July 2017 (1)

- June 2017 (3)

- May 2017 (1)

- March 2017 (2)

- February 2017 (1)

- January 2017 (5)

- December 2016 (2)

- November 2016 (2)

- June 2016 (1)

- March 2016 (1)

- December 2015 (1)

- July 2014 (1)

- February 2014 (1)

- January 2014 (4)