Documenting the Dispatched: A Case Study on the Preservation of Two Welsh Plaster Cast Copies

10 June 2019

A rough draft of a developing idea, artists use maquettes for structural planning, testing forms, and determining the feasibility of a finished statue. But what is to be done with them afterward? While most maquettes end up in the scrap heap of history, occasionally some are preserved to the present. As a sort of 3D “sketch”, these statuettes have value in their own right by giving a glimpse into the artist’s planning process and can offer insight and meaning to it – especially when the statues they were modelled for no longer exists.

In this post, two such maquettes created by Welsh artists are examined by co-authors Sara Bohuch and Aly Singh.

In 2018 two plaster maquettes were allotted to the co-authors of this blog post (and the associated ICON19 poster). Though both possessed many differences from one another, the common thread they had was the original intent of their creation: that these were not objects created to be kept for their own sake. Despite this supposedly disposable nature, these objects possessed such an interesting history that the whole treatment experience could not be contained on a single poster.

The Newport Museum Maquette

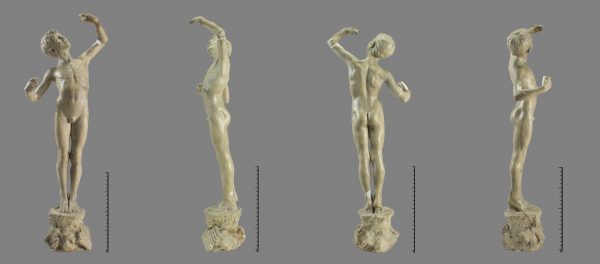

When the smaller maquette of a young boy came to the Cardiff University Conservation department, very little was known about it. It arrived dusty and disarticulated, with breaks and scrapes indicating a rather dramatic fall in its past. Research could only be conducted on three areas: the visible signature on the base, the statue’s form, and the materials used to construct it. Results from these areas would tie in with establishing the significance of the maquette, which would in turn feed into a treatment plan.

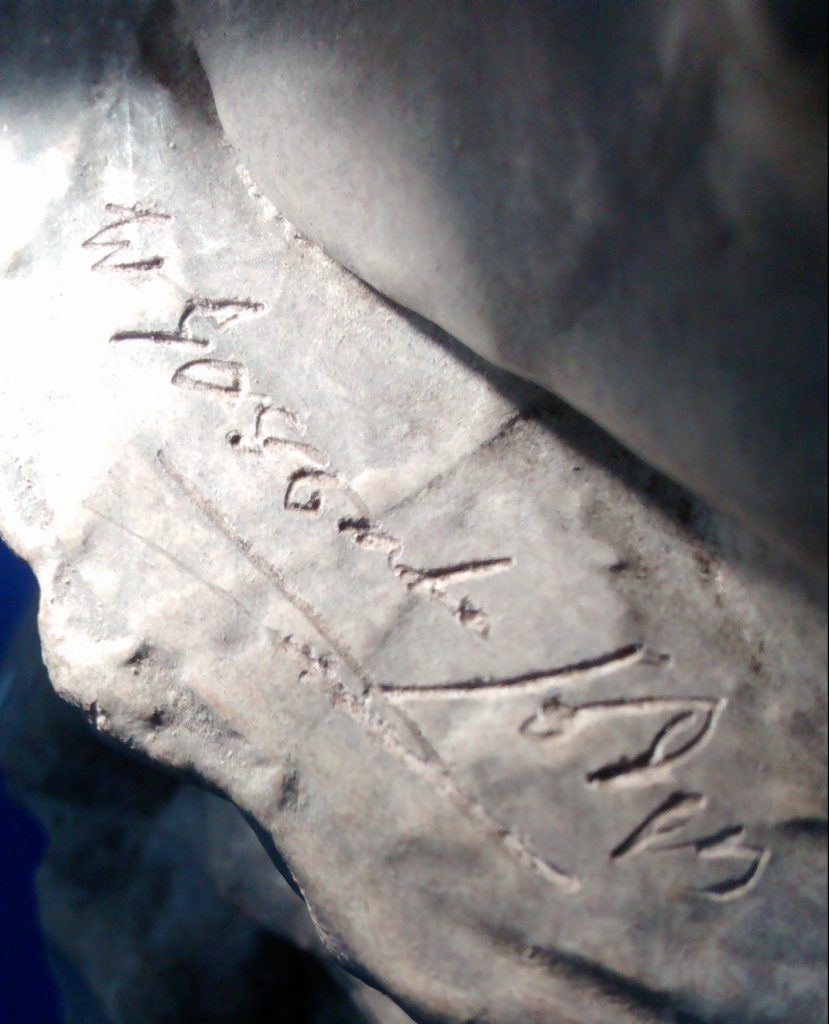

The first step was to examine the largest indicator for significance: the signature in the base. Signed ‘W. Goscombe John’, this pointed to the sculptor of the maquette being a well-known Welsh artist of the full name Sir William Goscombe John.

Goscombe John was an artist involved in the British New Sculpture movement of the late 19th/early 20th centuries. His work therefore focused more on the naturalistic expression of the human form. This can be observed when examining his other works throughout Wales, such as “The Elf” in the castle gardens of St Fagans National Museum of History, and the St David statue at Cardiff City hall. He was born in Canton, a district of Cardiff, and he grew up involved in the art and restoration of the area. He apprenticed to Thomas Nicolls, the sculptor responsible for the animal wall by Cardiff Castle, and later went on to study with Rodin in Paris. He was knighted in 1911 and died in 1952 at the age of 92.

The signature went a long way in establishing significance but didn’t give a whole picture. The second point for examination was therefore the way that the maquette was fashioned. Research showed that its distinctive form tied it to various similar statues and casts across the country. One of the most well-known is ‘Joyance’, a statue that can be seen in the water fountain at Thompson’s Park in his hometown of Canton. This is the most well-known because this is the version that has been stolen the most.

‘Joyance’ was first installed in the park in 1899 and was made of bronze. This was stolen in 1973 and replaced with a replica, and then the replica was stolen in July 2010. The version that you see in the park today is the fourth version since it was originally unveiled. Currently it is made of plastic and was installed in February of 2011.

The maquette conserved is not an identical copy of ‘Joyance’, as there are minute observable differences. Instead, it is most akin to the 1901 bronze statue ’Pan’, which can be found in the Tate’s collections in London. This is because of the details seen around the base, such as the presence of pipes, as well as the fact that there is nothing being held in the hands of the figure. The plaster cast being conserved at Cardiff still possesses the visible casting seam down the leg, which has not been filed down before finishing.

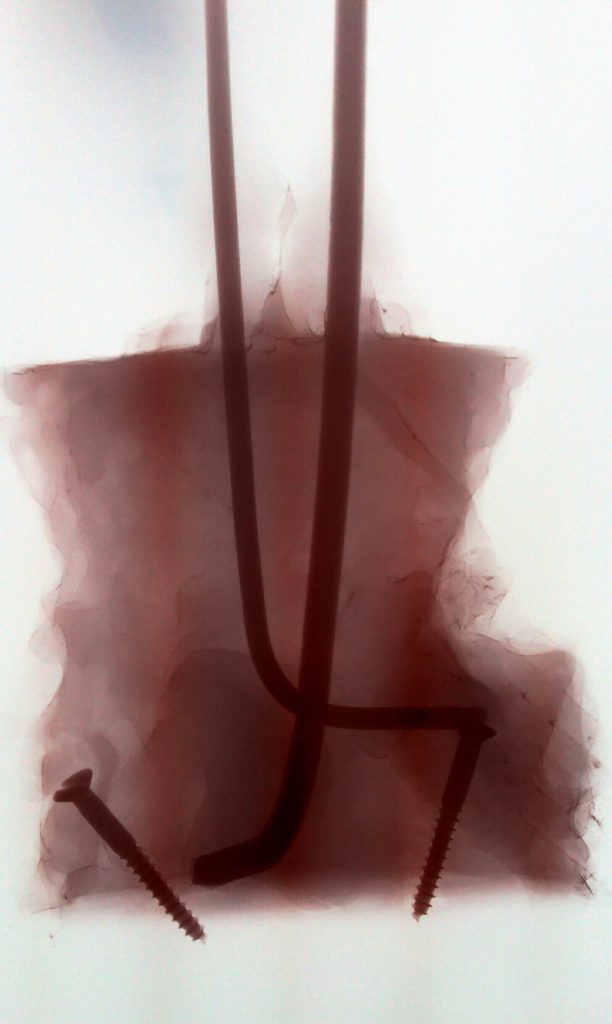

A final step to corroborate this information uncovered was material examination. FTIR examination of a disarticulated piece showed its material identity being plaster of paris. A UV fluorescence analysis showed the presence of a linseed oil coating (which fluoresces yellow green) and plaster base material (which has no fluorescence whatsoever). This coating covered the whole of the statue, minus the reworked areas of the arms, and including the tops of the screw holes in the base. This showed that the screws were most likely put in before the statue was coated.

An x-ray of the base revealed the placement of the angled iron screws, which was near the wire armature. This purposeful inclusion hinted at a specific customized stand that it was designed to fit into, which it had become separated from in its past.

All the above feeds into a treatment plan that accommodates the maquette’s history, materials, and object needs. Though beginning life as a ‘3D sketch’, later modifications like the screws and the signature point to a desire for it to last beyond the planning stage. Therefore, the piece needed to keep not only the screws themselves but be returned to the point before the most recent material damage occurred. This meant the arm needed to be adjusted, the elbow returned to its original placement, and the largest areas of the material loss filled. And, of course, for it to receive a surface clean.

The Museum of Cardiff Maquette (In Progress)

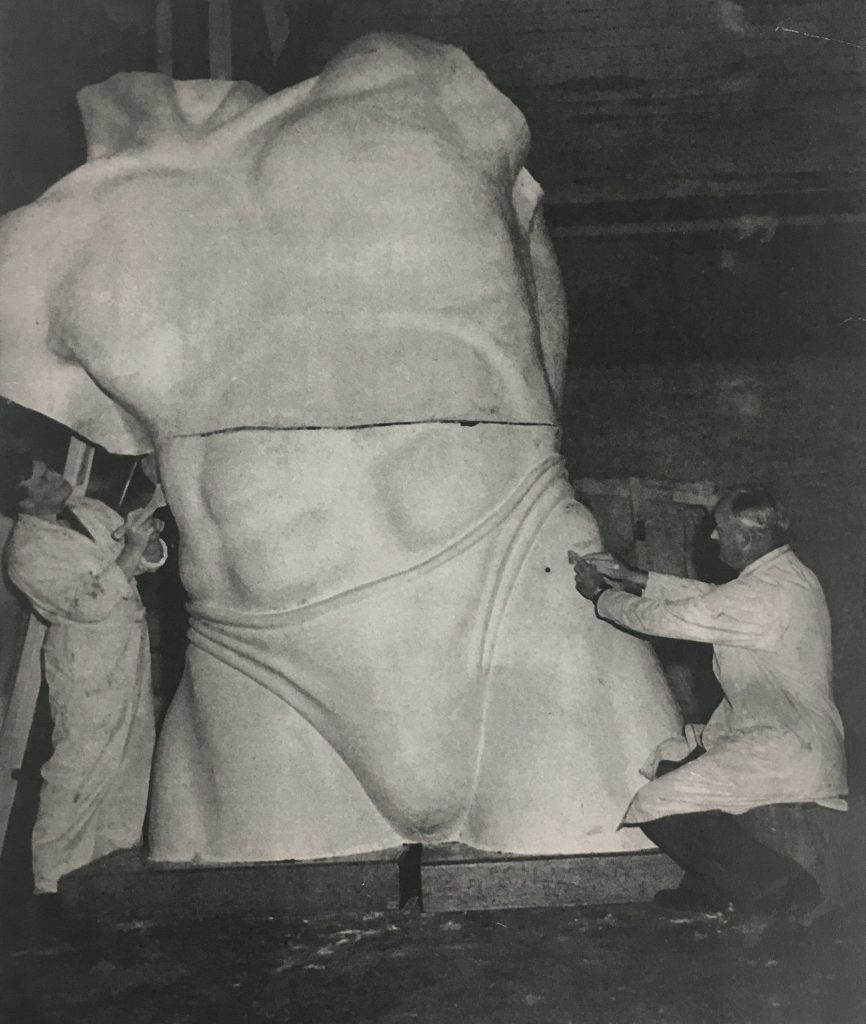

In 1958 the Empire Games came to Cardiff, and with them the eyes of the nation. In celebration of the Games and athletes, Howell’s Department store commissioned and erected a 36’ statue of a javelin thrower on its roof. Designed and constructed by the local ABC studios, several 9:1 scale casts were made to test materials, structure, and measurements. These 4’ scale casts were made of a wooden frame, jute webbing to build out the shape, and unfinished plaster. Of these casts only one is known to survive to the present, and it is currently found in the collection of the Museum of Cardiff (formerly the Cardiff Story Museum).

Originally left in a closet for several decades, this cast was found and donated to the Museum of Cardiff long after the Empire Games had concluded. The only known remaining cast copy, it arrived into the Cardiff University Conservation department in 2010 in dire need of structural repairs. Emergency conservation work was undertaken, which included the separating of the cast’s two halves in order to structurally stabilize the shattered ankles and brace the base. The interior was lined with a cotton textile and Paraloid B72 to secure the cracking plaster. The right arm and hand were also temporarily stabilized before the cast was screwed closed once again.

The unique history of the cast, combined with its condition, meant that determining the treatment would not be a straightforward task. To begin, the stakeholders had different opinions – suggestions of external bracketing and plaster dipped wadding to infill the leg voids came from the local historian who donated the cast, in order to remain sympathetic to the original construction methods. Meanwhile, the curators requested a reversible, non-visibly intrusive treatment that would not add excess weight to the cast. Examining the cast also showed pencil marks outlining the internal frame, which were to be conserved, alongside the surface damage inflicted by several decades in a closet under a leaky roof.

From a condition and conservation perspective, it was quickly determined that reopening the cast was not feasible. The screw holes were already beginning to crumble, and the shattered ankles meant there was no guarantee the halves would separate and rejoin without further damage. As it were, the emergency structural work undertaken in 2010 by Cardiff University Conservation senior lecturer Phil Parkes had dramatically increased the stability of the cast and only small updates were required.

To begin, the unfinished surface of the cast precluded wet cleaning, due to the risk of dirt migrating into the plaster and staining it further. The large surface area of the cast and the uniform dirt layer lead to the suggestion of laser cleaning, and testing indicated this could be done safely with the Nd:YAG 1064nm Q-switched laser in the lab, at a fluence of 0.01 J/cm2, returning the cast to its original plaster white colour. Areas of loss on the face and chest would be left untouched to show its time in storage – something which undoubtedly lead to it being saved from destruction after the Games had concluded.

As for the structural work, carbon fibre support rods were first considered, but the narrowness of the ankles, lack of maneuverability, and shape of the leg voids meant they would not provide adequate support to the ankles themselves. Infilling the legs to a few inches above the ankles proved the path forward, and upon weighing the pros and cons of different materials with the curator Paraloid B72 mixed with lightweight silica spheres was decided upon. The right arm – first stabilized with Paraloid B72 in 2010 – would be repositioned to the correct angle, and consolidation of the flaking plaster would also be done with Paraloid B72. Other than further consolidation of the base with the epoxy resin Araldite 2015, all structural repairs can be reversed if required.

Conclusion

Both maquettes are made of plaster, both were produced locally, and both are significant to Cardiff’s history. It is more than clear that these two maquettes are unique and individual insights into the artistic process. As with every object that crosses a conservator’s bench, they required a thorough understanding of their significance and history in order to provide the best possible treatment pathway.

Working with these maquettes provided a wonderful learning opportunity for Sara Bohuch and Aly Singh, and they would like to thank the Museum of Cardiff and Newport Museum curatorial teams, Phil Parkes, Jane Henderson and the entire Cardiff University Conservation department.

- March 2024 (1)

- December 2023 (1)

- November 2023 (2)

- March 2023 (2)

- January 2023 (6)

- November 2022 (1)

- October 2022 (1)

- June 2022 (6)

- January 2022 (8)

- March 2021 (2)

- January 2021 (3)

- June 2020 (1)

- May 2020 (1)

- April 2020 (1)

- March 2020 (4)

- February 2020 (3)

- January 2020 (5)

- November 2019 (1)

- October 2019 (1)

- June 2019 (1)

- April 2019 (2)

- March 2019 (1)

- January 2019 (1)

- August 2018 (2)

- July 2018 (5)

- June 2018 (2)

- May 2018 (3)

- March 2018 (1)

- February 2018 (3)

- January 2018 (1)

- December 2017 (1)

- October 2017 (4)

- September 2017 (1)

- August 2017 (2)

- July 2017 (1)

- June 2017 (3)

- May 2017 (1)

- March 2017 (2)

- February 2017 (1)

- January 2017 (5)

- December 2016 (2)

- November 2016 (2)

- June 2016 (1)

- March 2016 (1)

- December 2015 (1)

- July 2014 (1)

- February 2014 (1)

- January 2014 (4)