Bugging Out: IPM of an active collection

5 October 2017

Although museums, galleries and archaeological sites provide the bulk of our work at Cardiff University it is important to remember, as a conservator in training, that cultural objects requiring treatment come from many sources. The treatment of these objects may present interesting challenges especially if they are still in active use. The case below highlights some of the constraints about working with an actively used collection and describes how we overcame the challenge.

Over the last year Cardiff University MSc Conservation Practice students Devin Mattlin, Chloe Pearce and I have been involved in the insect pest management (IPM) of a West African instrument collection held by Cardiff University’s School of Music. The collection includes 36 drums, 20 of which belonged to the instructor, 2 bolons (a 4-string harp like instrument similar to a kora – see below) and a variety of wooden and gourd instruments. Loss of material on the drums and bolons, among other evidence, led the music department to believe they had an insect pest infection. They got in touch with Cardiff University’s Conservation and Care of Collections Department to treat the problem and save the drums from further damage. Devin was appointed project lead and recruited Chloe and me to help her.

We began with an investigation of the instruments and their storage environment. The instruments are made from wood, rope, animal hide and some are, or had been, lined with fur. After an initial inspection in which we took samples from the debris around the room we decided to individually assess each of the 36 drums. Each drum was given a number and many exhibited the signs of a pest infection including damaged fur, frass, pupation cocoons, and adult moths. Multiple samples were taken from each drum and bagged according to number, then each drum was qualitatively graded between 1&4 based on the severity of the infestation, with 1 showing no signs of infestation and 4 showing extreme signs of infestation. Although not very scientific this method allowed us to quickly assess which drums we would need to prioritise for treatment and suggested that the drums heavily lined with fur and fabric were the main targets of the pests. A beaded gourd instrument exhibited bore holes suggestive of woodworm (Anobium Punctatum) damage however it was the only instrument in the collection to show these signs and it was possible the damage was not recent. Pest traps left by Jane Henderson earlier in the year were replaced and taken back to the lab for analysis along with our samples.

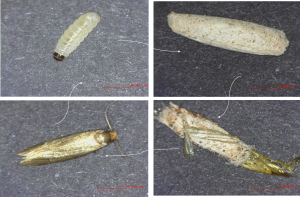

Our condition ratings were validated early on when the sample bags from two of the drums we’d graded as 4 contained live larvae. This amusing surprise meant that we now had samples from every phase of life to help identify the pest. Examination of the samples using http://www.whatseatingyourcollection.com as a reference revealed our culprit to be the webbing clothes moth (Tineola bisselliella). This species of moth feeds on animal proteins from wool and fur in its larval stage, which was consistent with the damage present on the instruments. The larvae hatch from eggs, then once they have eaten enough, they pupate in a silk cocoon until emerging as adult moths. The diagram below shows this life cycle.

Now that we had identified the problem we could concentrate on our main objective: to treat the infestation without causing damage to the collection or interrupting the collection’s use by the music department students. At a rehearsal which Devin and I attended the students gave a powerful performance, showing us that the instruments were used with bare hands and making it clear that most of the drums were needed. This meant that the period we had to conduct a treatment was limited to a few weeks during the exam period and since this was a collaboration between the music and conservation departments there was no budget allocated to the treatment. These constraints had to be factored in when deciding on a treatment course, ruling out nitrogen treatment because of its high cost, time and space requirements. We also decided against treating with Constrain because it could potentially damage the animal skins and harm the students using the collection, and finally pheromone traps were ruled out because of their low success rate at removing an infestation. Freezing, however, matched the criteria of being safe for the students and environment, cost free, and low risk to the objects. At the temperatures of the lab’s chest freezer, between -20 and -22oC, all the moths could be killed in around 10 days. Given these reasons and the simplicity of execution it was decided that freeze treatment was the way forward.

Due to the size of the collection and limits of equipment we had to prioritise freeze treatment to the 4 drums we had rated as a 4 and the gourd covered in bore holes. These were double bagged and taped to prevent the ingress of moisture during treatment then placed in the freezer, in two batches, for 15 days each. Once complete each instrument was fine cleaned by hand using a museum vacuum cleaner, brushes, bamboo skewers, and tweezers to remove any insect material and frass. The same fine cleaning was carried out an all the instruments that did not undergo freeze treatment, much to the dismay of one of our museum vacuums whose motor literally burnt out during treatment, setting off the smoke alarms and causing the evacuation of the music department during deadline season. Once our lost comrade was replaced we were, surprisingly, let back into the music department to finish cleaning each instrument and the store.

The freeze treated instruments were moved back to the now clean store room and fresh pest traps were placed inside. Monitoring is currently ongoing with the only moths spotted so far on the 2 bolons. These instruments have been quarantined and are now undergoing the same freeze treatment as the grade 4 drums. Devin and I will continue with monthly inspections to determine how successful the treatment was. It has been very interesting and highly beneficial to work within the constraints of the owner’s requirements and is a valuable skill to learn as a budding conservator.

Photos taken by Devin, Dean, and Chloe.

- March 2024 (1)

- December 2023 (1)

- November 2023 (2)

- March 2023 (2)

- January 2023 (6)

- November 2022 (1)

- October 2022 (1)

- June 2022 (6)

- January 2022 (8)

- March 2021 (2)

- January 2021 (3)

- June 2020 (1)

- May 2020 (1)

- April 2020 (1)

- March 2020 (4)

- February 2020 (3)

- January 2020 (5)

- November 2019 (1)

- October 2019 (1)

- June 2019 (1)

- April 2019 (2)

- March 2019 (1)

- January 2019 (1)

- August 2018 (2)

- July 2018 (5)

- June 2018 (2)

- May 2018 (3)

- March 2018 (1)

- February 2018 (3)

- January 2018 (1)

- December 2017 (1)

- October 2017 (4)

- September 2017 (1)

- August 2017 (2)

- July 2017 (1)

- June 2017 (3)

- May 2017 (1)

- March 2017 (2)

- February 2017 (1)

- January 2017 (5)

- December 2016 (2)

- November 2016 (2)

- June 2016 (1)

- March 2016 (1)

- December 2015 (1)

- July 2014 (1)

- February 2014 (1)

- January 2014 (4)