When ends don’t meet: towards a “high wage” economy? (Part 3)

26 October 2021

In the third of a three-part blog series on household finances, the Wales Fiscal Analysis team present the latest picture of the labour market in Wales as the furlough scheme is wound down.

In Part 1 and Part 2 of this series, we looked at how tax increases, benefit cuts and a cost-of-living crisis are set to squeeze Welsh household incomes over the coming months. In this blog post, we look at the latest trends in pay and employment.

The end of furlough

As August 2021 came to a close, 46,000 employments were fully or partially furloughed in Wales (equivalent to a take-up rate of 4%), down from 247,000 at the beginning of July 2020. This number will have reduced further over the course of September.

On the face of it, a furlough “cliff-edge” has – for the most part – been avoided.

The vast majority of the 474,000 Welsh workers who were furloughed at some point over the past 18 months had already left the scheme when it was wound down at the end of September.

It was not always obvious that this would be the case, however. A plan to prematurely bring the scheme to an end prior to last year’s Winter lockdown was – eventually – shelved.

Nevertheless, the steady decline in the number of furloughed employments over the summer means that the Office for Budget Responsibility is likely to make a downward revision to its forecast of UK-wide unemployment when it publishes its latest set of economic indicators tomorrow.

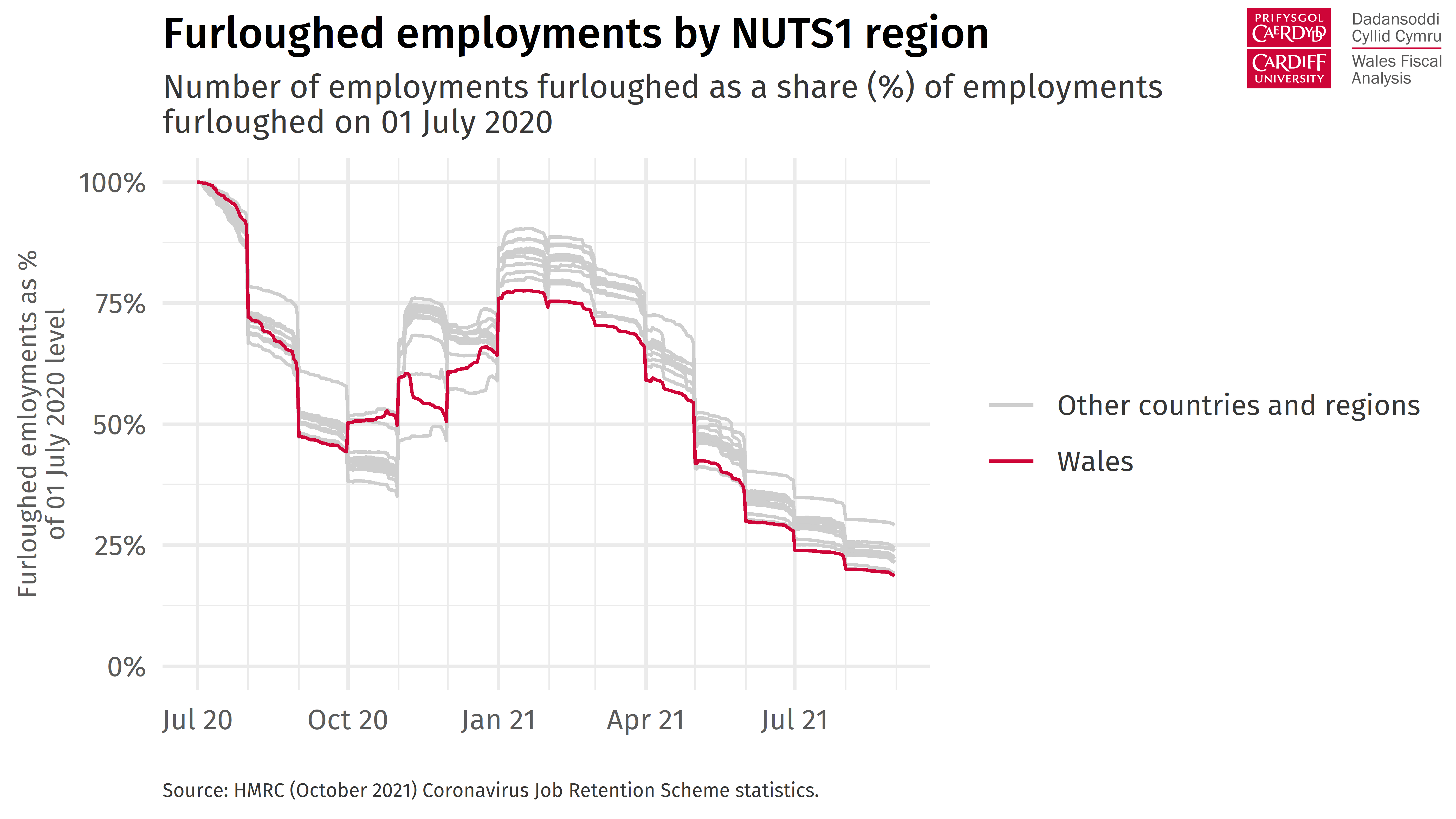

And there are some indications that Wales outperformed the rest of the UK when it came to bringing people off the job retention scheme.

Equalising take-up rates at their 01 July 2020 level – when regional data first became available – the proportion of eligible employments furloughed in Wales has consistently fallen faster than in Scotland, Northern Ireland, and the English regions (apart from October 2020).

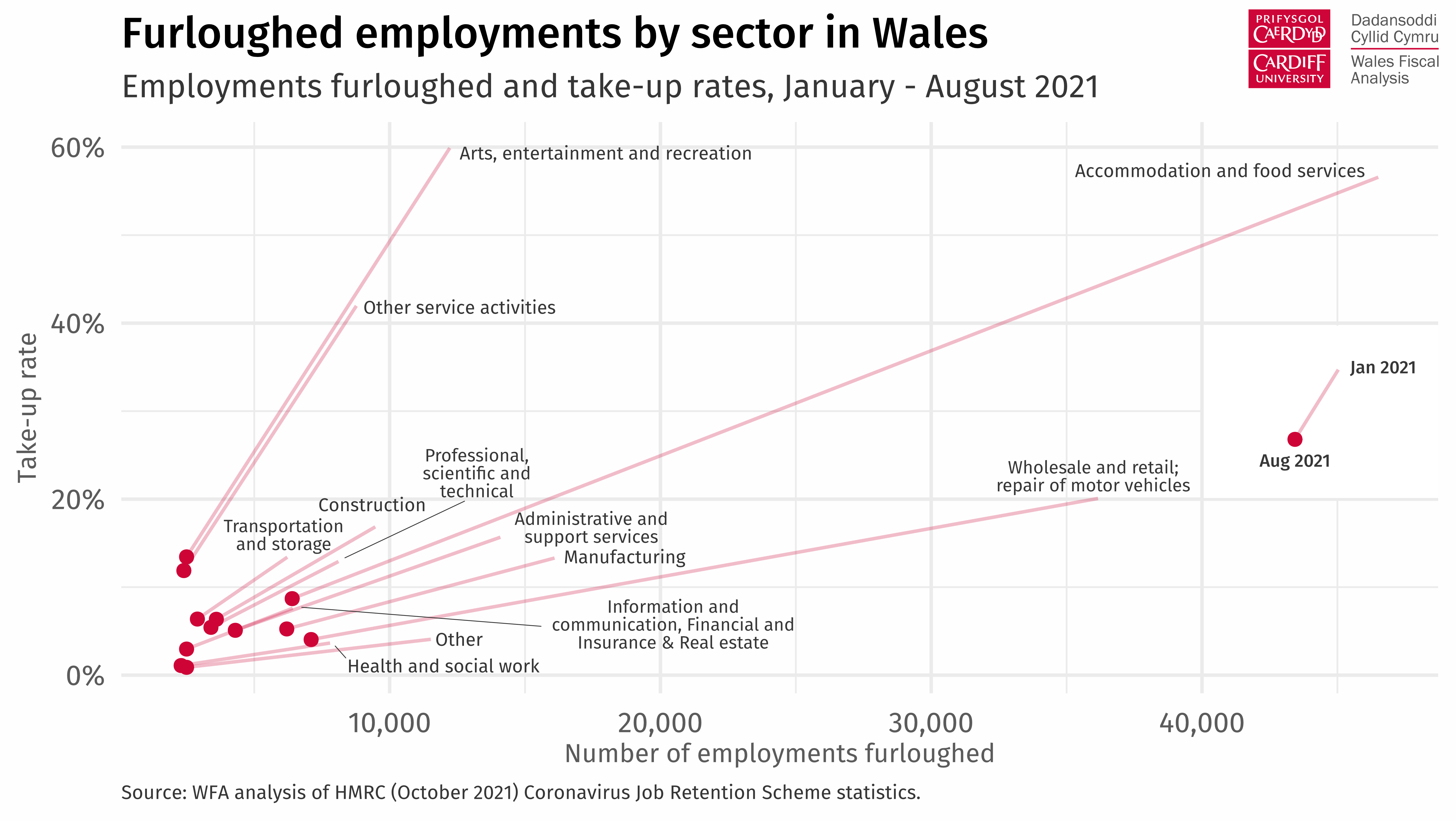

However, there remains considerable variation between sectors.

Even at the end of August, take-up remained stubbornly high (14%) among those working in the arts, entertainment, and recreation sector (equivalent to 2,500 employments in Wales).

And although the scheme’s take-up among those working in the accommodation and food services sector fell from its 55% high in January 2021 to less than 10% in August, this still equates to 6,400 employments furloughed according to the most recent data.

A “high wage” economy?

HMRC publishes real-time estimates of payrolled employments for the countries and regions of the UK. Although this only captures data on earnings which are paid via Pay As You Earn (PAYE), it is nevertheless the best source for up-to-date information on pay and employment for smaller geographies.

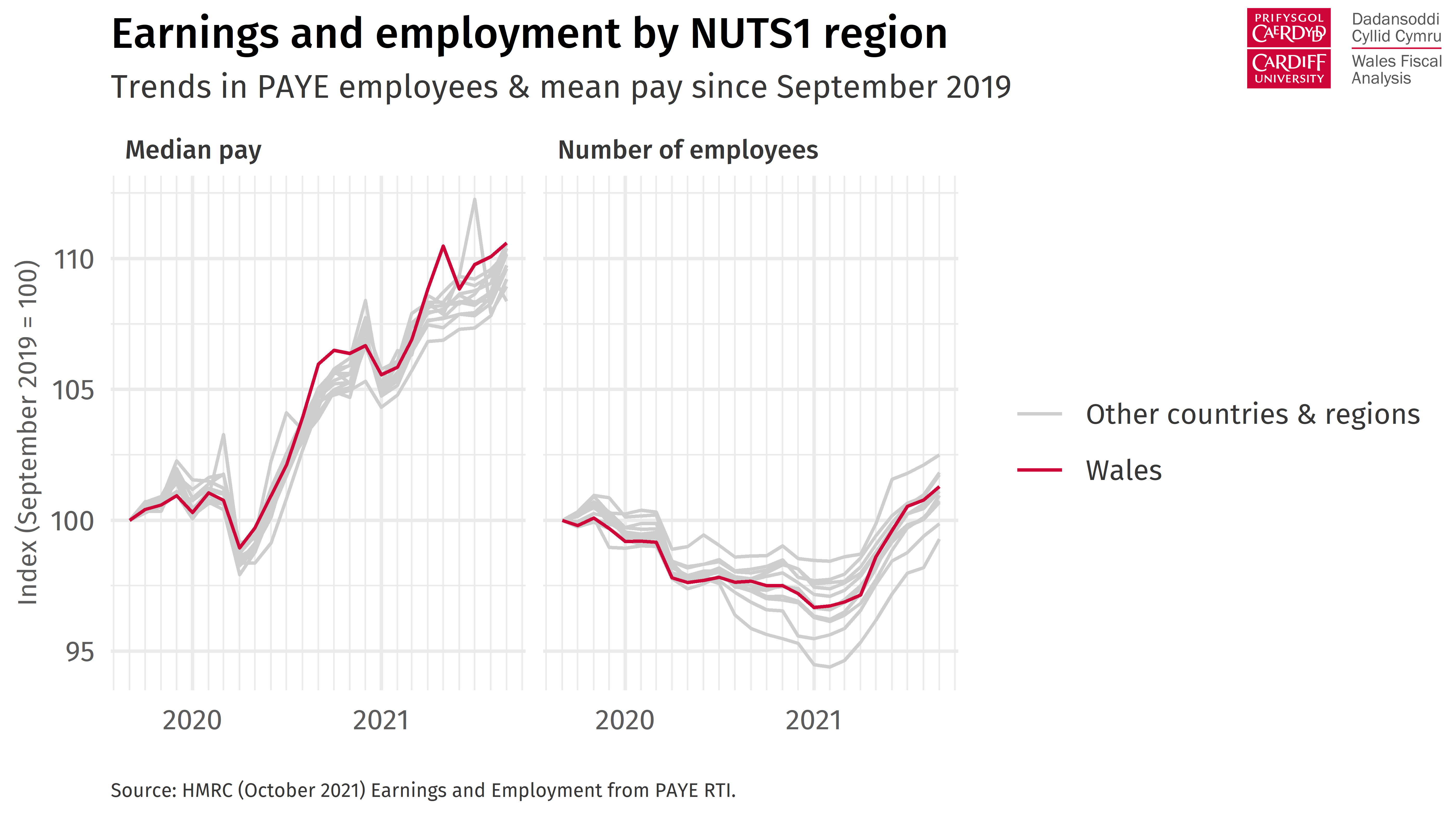

After a sharp drop at the beginning of the pandemic, Welsh employee numbers have now recovered their pre-covid levels.

Median pay for Welsh employees is up 10% compared to the same period two years ago – a relatively high growth rate by historic standards.

However, this may well overstate the actual increase in pay, particularly if – as has been suggested elsewhere – younger and lower-paid workers are more likely to have dropped out of the workforce during the pandemic, thereby pushing up the median pay measurement.

And there is some evidence to suggest that recent wage growth primarily reflects labour shortages in specific sectors rather than economy-wide pressures.

The decision to increase the National Living Wage for those aged 23 and over to £9.50 an hour from April 2022 is a welcome one. It continues the trend seen over the past few years, whereby increases to the National Living Wage have outpaced growth in average earnings.

It would, however, be a mistake to suggest that this compensates for the reduction to Universal Credit earlier this month, not least because the population groups affected by both policies do not necessarily overlap. In addition, a high marginal withdrawal rate means that the actual increase in take-home pay for someone earning the National Living Wage whilst on Universal Credit will be considerably smaller.

From a budgetary perspective, there is some good news for the Welsh Government.

Wales has seen a faster recovery in employee numbers and faster earnings growth compared to the UK average over the past 24 months. Growth in median employee pay exceeded that seen in Scotland, Northern Ireland and all nine regions of England over the same period.

This matters because, following the devolution of tax powers, in-year growth in non-savings, non-dividend income tax revenues need to keep up with England and Northern Ireland to ensure that the Welsh Budget does not lose out as a result of the block grant adjustment.

The early signs are promising.

The future workforce

In a speech to the Conservative Party conference earlier this month, the Prime Minister touted the merits of transitioning to a “high-wage, high-skill, high-productivity economy”. As if to underline the point, this was juxtaposed with a reference to the “same old broken model … enabled and assisted by uncontrolled immigration”.

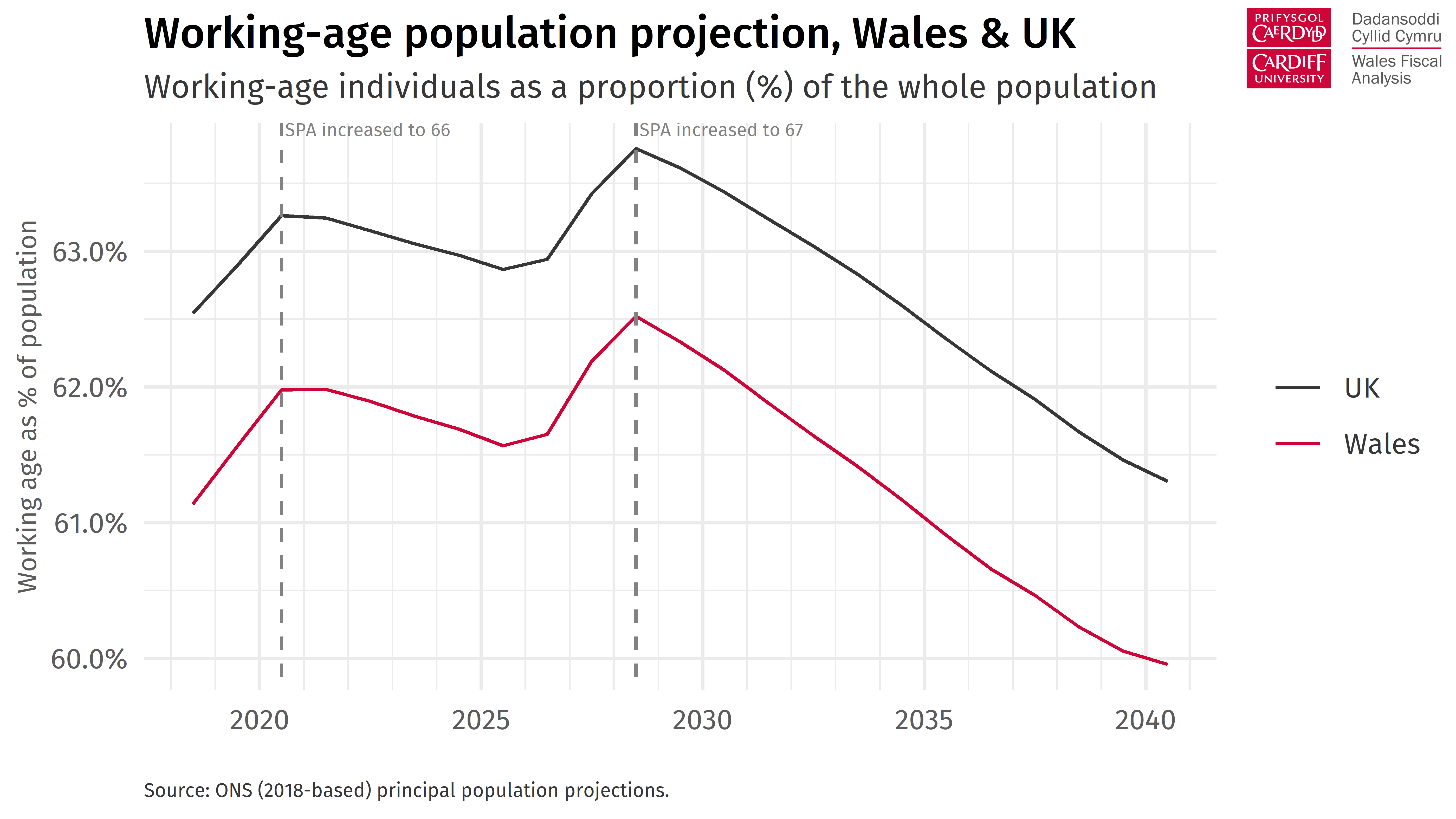

One thing is clear, migration (both within the UK and from abroad) must continue to play an outsized role in Wales’ employment growth over the coming years.

The natural change in Wales’ population is already below zero meaning that more people die in any given year than there are being born. So far, Wales’ population growth has been sustained by inward net migration.

By 2040, the proportion of the population who are at working-age is projected to fall below 60% despite multiple increases to the state pension age – a fact recently highlighted by the Economy Minister when setting out his vision for the future of the Welsh economy.

In this context, the decisions made by successive UK government to shift more of the tax burden onto working-age individuals by preferring national insurance to income tax increases appear even more ill-thought.

***

The Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme has arguably been one of the success stories of the UK government’s pandemic response – though the scheme was, in part, a necessary reaction to the relative ungenerosity of standard unemployment benefits in the UK.

Although there is some evidence that earnings growth has picked up recently, it remains to be seen whether this will be sustained and economy wide. A decade of pay stagnation, looming tax rises and increases to the cost-of-living mean that any real increase to purchasing power will be limited.

For many, pressures on household finances are unlikely to abate soon.

- December 2023

- November 2023

- August 2023

- February 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- September 2022

- July 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- January 2022

- October 2021

- July 2021

- May 2021

- March 2021

- January 2021

- November 2020

- October 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- October 2019

- September 2019

- June 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- December 2018

- October 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- April 2018

- December 2017

- October 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- Bevan and Wales

- Big Data

- Brexit

- British Politics

- Constitution

- Covid-19

- Devolution

- Elections

- EU

- Finance

- Gender

- History

- Housing

- Introduction

- Justice

- Labour Party

- Law

- Local Government

- Media

- National Assembly

- Plaid Cymru

- Prisons

- Rugby

- Theory

- Uncategorized

- Welsh Conservatives

- Welsh Election 2016

- Welsh Elections