What do the latest population projections tell us about Wales?

30 October 2019

Earlier this month, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) published their latest population projections for the UK. Despite its seemingly ‘dry’ nature, this data is widely used by researcher and policy makers alike to inform fiscal projections, identify future demand for hospital and school places, and estimate the future cost of state pensions.

Though much of the findings were overshadowed by the hubbub of political developments, the data reveals some important insights into Wales’ demographic trajectory and shows – for the first time – a projected decline in Wales’ population in the near-term.

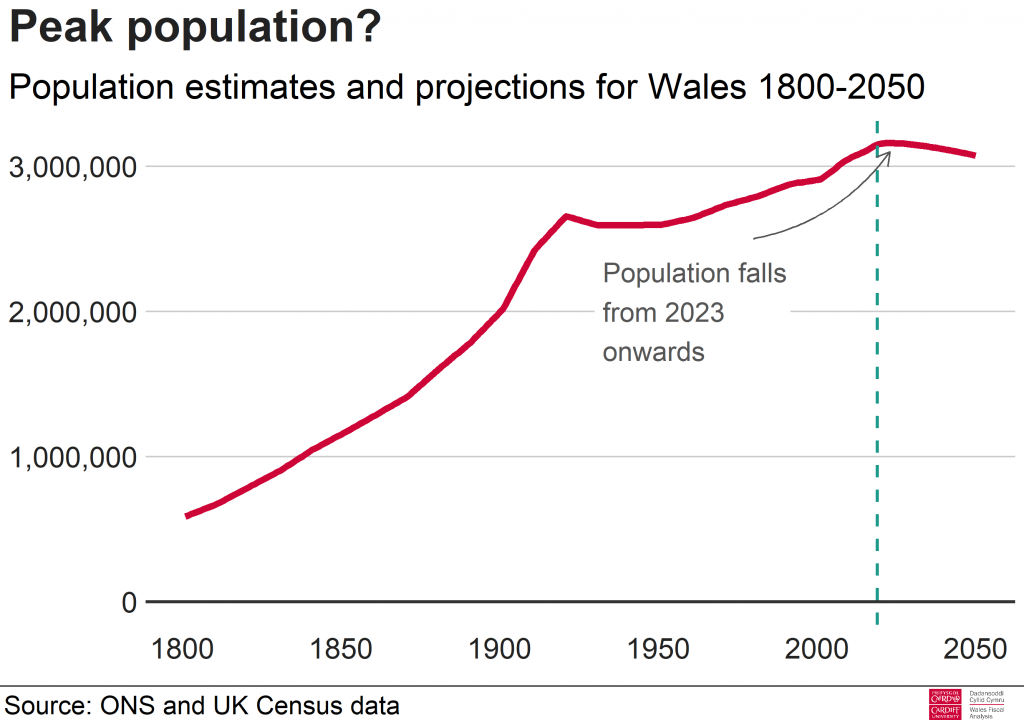

Peak population?

According to the principal projection, the population of Wales is set to peak at 3.16 million in 2023, more than two decades earlier than previously projected. The population of the UK as a whole is expected to continue growing, albeit at a slower pace than previously.

If these projections are borne out, Wales is on the verge of its first period of sustained population decline in nearly a century.

The last time Wales experienced a prolonged episode of population degrowth was during the 1920s. Coal exports remained a significant contribution to the Welsh economy throughout the early 20th Century; however, increased competition from abroad and the availability of cheaper substitute fuels had started to depress demand for Welsh coal. Unemployment amongst coalminers rose from 2% in April 1924 to 28.5% in August 1925. Faced with bleak economic prospects at home, many decided to emigrate. Wales lost nearly 400,000 people between 1925 and 1939.

If these projections are borne out, Wales is on the verge of its first period of sustained population decline in nearly a century.

Fast forward to 2019 and the headline unemployment rate is at historically low levels with Wales’ economic activity levels at an all-time high — what is driving the population decline this time?

In truth, Wales’ natural population change has been negative for some years, meaning that there are more deaths than births in any given year. So far, population levels have been buoyed by inward international migration and migration into Wales from other parts of the UK.

However, a projected drop in inward international migration over the next decade and a continued decline in fertility rates suggests that the net effect of inward migration will not be enough to offset the natural change in population from 2023 onwards.

Wales is likely to experience population decline ahead of other parts of the UK as it has relatively lower levels of inward international migration. In 2018, the share of Wales’ population born outside of the UK was 6.1%, whereas on a UK-wide basis, a full 14.3% of the population were born outside the UK.

Should we be concerned by this development? Not necessarily, the Malthusian belief that the world’s population would continue to grow exponentially until it exhausted the sustenance needed to sustain itself is no longer conventional wisdom. Many experts believe that the world’s population could peak before the end of this century.

Nevertheless, the composition of Wales’ future demographics and, in particular, trends in the pensioner, working age and child population will play a critical role in the debate around how to sustainably fund our local and public services.

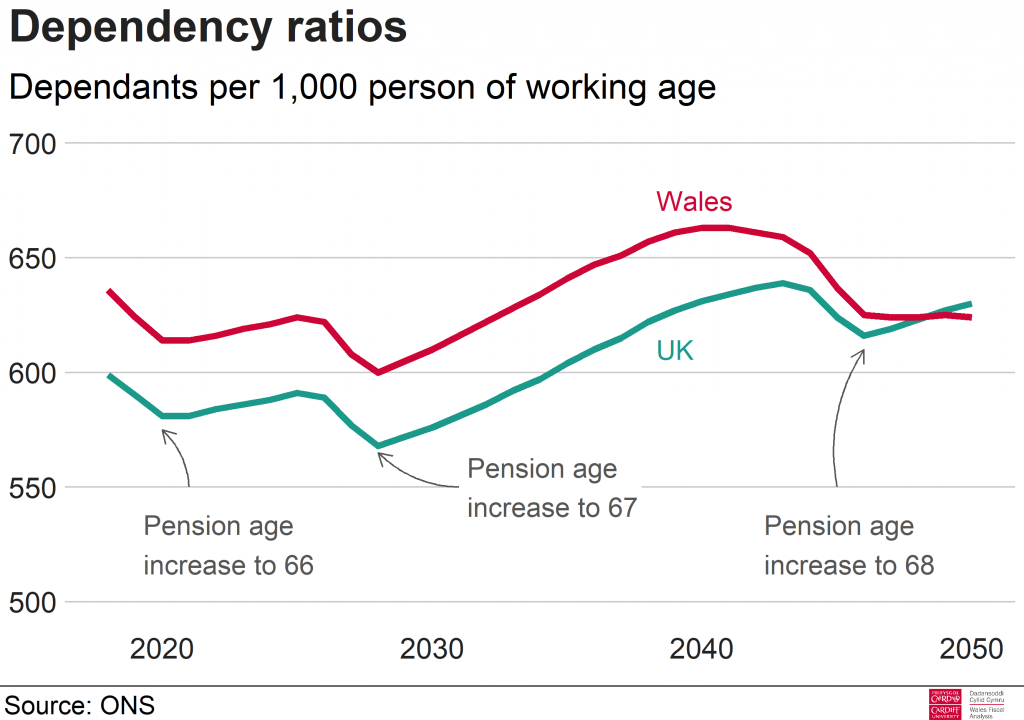

Dependency ratios

Peoples’ need for public services and their ability to contribute through taxes varies across their lifespan. In general, health and social care spending is highest in old age whilst education spending per head is highest for those under 25. Meanwhile, total tax paid by the average person in Wales peaks when that person is aged 46. A dependency ratio measures the number of children and pensioners per person of working age.

It is no secret that Wales’ population is older than the UK average. This is reflected by the fact that Wales has a higher dependency ratio, with 625 dependents per 1,000 members of the working age population compared to 590 across the UK.

Wales’ over 65 population is now projected to grow at a slower pace than the UK average (as a share of the total population, this cohort will continue to grow relatively quicker). However, since the under 16 cohort in Wales is projected to grow relatively slower than the UK average, the gap between the dependency ratios remains broadly unchanged over time.

The population projections indicate a convergence in dependency ratios around 2050. Although the reasons behind this are not entirely clear, it happens to coincide with the transition of the cohort that is currently in their thirties to pension age. This cohort currently accounts for a smaller share of Wales’ population compared to the UK average. However, it is not obvious that this is a cohort-specific trait. The projections may not fully reflect the fact that there is a net outflow of people from Wales to other parts of the UK among 30- and 40-year olds, a trend that is reversed among those aged 50 and over. Ultimately, this anomaly highlights the difficulty of generating reliable population projections far into the future.

The troughs in the chart coincide with the planned pension increases to 68 over the next decades. This is expected to have a sizeable impact on dependency ratios. The population projections are based on the UK government’s original plans to gradually increase the pension age from 67 to 68 between 2044 and 2046. However, this increase is now set to take place between 2037 to 2039, seven years earlier than previously planned.

Of course, planned increases to the state pension age may yet be subject to change, especially if recent trends, which have seen UK life expectancy fall, are sustained.

Population degrowth and the block grant

Wales’ relative population growth is intrinsically tied into the operation of the Barnett formula. This formula is used to determine the size of the block grant, the main source of funding for the Welsh Government.

An in-built property of the Barnett formula is that if spending is growing in England, it results in convergence in per-person spending over time between England and Wales. This is because the same pounds-per-person increase in spending in England and Wales representsa smaller percentage increase in Wales (see this report for a more technical expnantion). This is the infamous Barnett Squeeze effect, as emphasised by the Hotham Commission report.

One of the factors determining the rate of convergence is differences in the rate of population growth between Wales and England. This is because the Barnett formula only determines changes in the block grant from year to year, reflecting the latest population shares; the size of the previous year’s grant that constitutes the majority of the current grant is not adjusted to account for the new population ratio. If the Welsh population grows relatively slowly, the rate of convergence decreases. Put simply, the Welsh block grant is spread between fewer people, which is good news for the real spending power of the Welsh Government.

Unfortunately – as is often the case – it is not all good news for Wales. The mechanism for adjusting the block grant downwards to account for tax devolution works the other way. Slower population growth will have an adverse impact on relative growth in devolved tax revenues.

The risks associated with slow population growth and its effect on tax devolution have long been recognised in Scotland, where slow population growth has been a feature of demographic trends there for some time. This was one of the reasons why Scotland opted for the Indexed per Capita (IPC) method when determining the block grant adjustment for tax devolution, as opposed to the Comparable Method (CM) agreed for Wales. The IPC method does not expose Scotland to the risk of relative population decline.

On a slightly less technical note, the working age population is now falling across Wales. This could also influence relative growth in devolved tax revenues as the working age population are the largest contributors of non-savings non-dividend tax revenue.

Projections not predictions

The ONS makes clear that its population projections are just that – “projections not predictions”. They are based on assumptions that are representative of what has happened in the UK to date. Of course, the past is not always a good guide to the present, let alone the future.

For those of us who wish to speculate, the ONS helpfully produce variants of its principal population projection to account for different assumptions about the future (e.g. lower/higher migration, lower/higher fertility rates and longer/shorter life expectancies). Researchers can use these projections if they think that an alternative future is more likely. For instance, were Brexit to lead to a stricter immigration regime, this would likely hasten the decline of the working age population in Wales.

Population and demographic trends are inexorably tied to questions about politics, economics and society. How can we sustainably fund our public services? What level of care can we afford future generations in old age? And how do today’s policies rank in terms of intergenerational fairness?

It is imperative that an understanding of our demographic trajectory is embedded within the political discourse and actively informs policymaking in Wales.

This blog post was prepared by the Wales Fiscal Analysis team, part of the Wales Governance Centre at Cardiff Univeristy.

Comments

3 comments

Comments are closed.

- December 2023

- November 2023

- August 2023

- February 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- September 2022

- July 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- January 2022

- October 2021

- July 2021

- May 2021

- March 2021

- January 2021

- November 2020

- October 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- October 2019

- September 2019

- June 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- December 2018

- October 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- April 2018

- December 2017

- October 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- Bevan and Wales

- Big Data

- Brexit

- British Politics

- Constitution

- Covid-19

- Devolution

- Elections

- EU

- Finance

- Gender

- History

- Housing

- Introduction

- Justice

- Labour Party

- Law

- Local Government

- Media

- National Assembly

- Plaid Cymru

- Prisons

- Rugby

- Theory

- Uncategorized

- Welsh Conservatives

- Welsh Election 2016

- Welsh Elections

Observation: You have put forward some really interesting demographic and economic projections based on your research, and it is evident from your data that nationalism, combined with isolationism has negatively promoted a pernicious social disease that has serious implications for the future economic and social health of Wales and indeed for the UK as a whole. I am minded to believe that Immigration, can and should be viewed in a positive way, a force for good rather than vice versa. Unfortunately, any rational arguments have often been distorted by opportunistic anti EU advocates who have played upon the fears of insecure folk who have felt abandoned by the political elite and authorities whom they blame for their plight, ( loss of traditional industries) where lack of investment in respective communities has influenced their daily lives and mode of thinking. This is obviously, a complex scenario, and there are no easy fixes, but Brexit, has been the catalyst for much of this latent anger, which has been raked and stoked up by opportunistic Brexiteers and right wing populist parties to further their ambitions to build a parody of Trump’s Mexican wall. In response to your question about how do today’s policies rank in terms of intergenerational fairness? There is clearly a problem, although, there is a danger of labelling certain generations as being biased. I am of a post 2nd WW war generation and I’m not sure whether or not I’m in the minority, sadly, there are some folk of my generation who hold some negative views towards immigration, yet, I have also met with and discussed many these issues with certain groups of youths,and their families, most of whom hold similar fanciful and misguided perceptions of progressing in a “Dad’s Army” society. The only way that this view can be effectively challenged is through communication and improved infra-structure and meaningful resources. The list is too long and to complex to discuss here.

Good luck

Paul R

I am shoulder to shoulder with you Paul R.. Your comments are spot on. I would add that these data would be even more intriguing if the probable impact of post Brexit funding and residency restrictions were factored in. It’s not a happy prognosis.