Would the North Berwick Witch Trials have happened without King James VI? A Counterfactual History (Lucy Martin)

22 September 2025

The subject of witches and witchcraft has long fascinated both historians and the public. From the infamous drama of Salem to the grim torture chambers of South Germany. One Scottish trial, however, stands out uniquely in European witch-hunting history – The North Berwick Witch trials of 1590-91. What made them unique was not just their brutality, but their association with a king, James VI of Scotland and (later) I of England. Following his encounter with the North Berwick witches, the young monarch authored Daemonologie (1597), a book that cemented his reputation as a witch-hunting king.

But how important was James really to the Berwick Trials? My dissertation set out to test whether the trials would still have happened without him. To this end, I employed counterfactual reasoning, a methodology more often associated with World War II than the witch-hunt.

What is counterfactual history and how does this approach help?

Counterfactual history is the ‘what if’ approach to historical scenarios – the idea being that by exploring alternative outcomes to events historians can evaluate their relative importance. Counterfactual reasoning is not new. Already in Antiquity, the philosophers Aristotle and Plato had put forward theoretical suppositions to consider imagined outcomes. While some counterfactual historians, such as Niall Ferguson, have courted controversy by placing the emphasis on alternative outcomes, in more recent times the testing of historical causality through the counterfactual approach has become a much more mainstream discipline.

Still, historians are often suspicious of ‘what if’ questions. Richard J. Evans, for example, criticised counterfactual history for being too speculative and potentially misleading. When used carefully however, it can be a powerful tool. My dissertation used what Allan Megill calls ‘restrained counterfactuals’: instead of imagining entirely new worlds – such as imagining one where James never became king – the approach carefully removed individual factors to see if events in the Berwick trials would still unfold. In other words, was James VI the driving force behind the North Berwick hunt, or just a figure who made them famous?

The traditional story

The North Berwick trials unfolded in 1590, just months after James VI’s voyage to Denmark to marry Anne of Denmark. On the journey home, his fleet was battered by storms, which some contemporaries claimed had been stirred up by witches. James had also encountered theologians and demonologists in Copenhagen, which fuelled his interest in the subject. When accusations of witchcraft surfaced in Scotland later that year, it was easy for them to be linked to the dangers he had faced at sea.

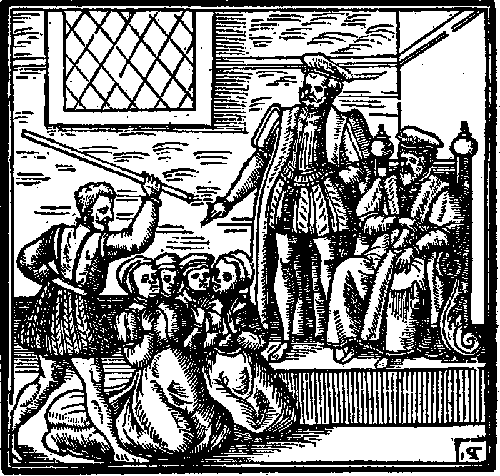

From the start, then, the narrative surrounding the witch-hunt was shaped around the king. The famous pamphlet Newes from Scotland (1591) shows him towering over accused witches, a divinely sanctioned judge rooting out evil. This image – and later his book Daemonologie – helped cement the idea that James not only believed in the reality of witchcraft but that he personally drove Scotland’s witch hunts.

This has been the interpretation advanced by some of Scotland’s most famous historians.. Christina Larner argued that James’s demonological writings shaped Scottish witch-hunting culture and legitimised the persecution. In popular culture too, James became known as the ‘witchfinder king’, a ruler whose obsession with the Devil left a bloody mark on history. But is this really the full picture?

What I found

The North Berwick trials began in 1590 when David Seton, a local official, accused his maid Geillis Duncan of witchcraft. Duncan was tortured until she confessed and gave up the names of others, including Agnes Sampson. This shows how accusations in Scotland usually started: not by the crown, but emerging within local communities Without Seton’s intervention, the chain of arrests and confessions that followed would never have begun.

James VI only became directly involved later. At first he was doubtful of the witches’ guilt, but his attitude changed after Agnes Sampson was interrogated in his presence. She repeated details of his wedding night that convinced him she had access to supernatural knowledge. That moment transformed James from a sceptical observer into a believer. Without it, his involvement might have remained minimal, and the trials would have looked very different.

Institutions also mattered. The Scottish Kirk provided a religious framework for understanding witchcraft, but it was the secular courts that made executions possible. The Kirk could excommunicate or order penance, but only the courts could condemn people to death. Without those legal structures, North Berwick would likely have remained a local dispute rather than a capital case.

James’s role, then, was to amplify rather than initiate the trials. His interrogations, the publicity of Newes from Scotland, and later his Daemonologie made the events nationally famous. But the evidence suggests that the trials did not depend on him. They would likely have happened anyway – just on a smaller, more local scale.

Conclusion

By removing one factor at a time – David Seton’s accusation, Agnes Sampson’s confession, or James VI’s involvement – I could weigh how much each turning point shaped the trials. This showed that they were not inevitable, but depended on these fragile conjunctions of persuasion, choice, and belief. Counterfactual reasoning, used this way, sharpens our understanding of cause and effect rather than distorting it.

Asking ‘what if’ may sometimes feel like we are playing games with the past. But in the case of the North Berwick witch trials, it reveals just how fragile the chain of events really was. If David Seton had not accused his maid Geillis Duncan, there likely would have been no investigation at all. If Agnes Sampson had not delivered a confession that personally convinced James VI, the king might have remained detached. And if the secular courts had not been able to impose capital punishments, the Kirk alone could never have turned suspicion into executions.

Testing these counterfactuals side by side highlights what mattered most. The trials were not the product of inevitability, nor the direct command of a king, but the result of contingent decisions and local structures. James’s involvement gave the trials greater visibility and legitimacy, but he did not cause it. Without him, the trials would still have taken place – only on a smaller and more local scale.

This approach challenges the familiar image of James as Scotland’s ‘witchfinder king’. Counterfactual reasoning shows that history does not always hinge on monarchs or great figures. Sometimes it depends on the choices of local officials, the words of an accused woman under torture, or the machinery of courts turning suspicion into death. The North Berwick trials remind us that history is shaped not just by the social and political elite, but the choices and voices of the many – and that imagining their absence from fragile moments in time can bring the past into sharper focus.