Today – on All Souls’s Day – Giovanna Thomas takes us through a virtual exhibition on the medieval reminder of Memento mori (Remember that you must die).

Introduction

It is often thought that the late medieval and early modern preoccupation with the macabre resulted from the constant presence of death and disease that people endured during their everyday lives. The arrival of the Black Death in 1348 and the subsequent death of over a third of Europe’s population meant that people were confronted with the reality of their own mortality on an unprecedented scale, creating a sense of existential anxiety. This was reflected in the Memento Mori (Latin for ‘remember you must die’) art produced during these periods, as this was a way of coping with the closeness of death by reminding people of the need to live a good, sin free life on earth in preparation for the afterlife. Memento Mori continues to be an object of fascination in current society, as it offers a unique and ‘fundamentally different’ perspective on the universal experience of death. Indeed, while macabre art emphasised the dangers of earthly vices, texts like the Ars Moriendi (Figure 1) highlight that people could find comfort in dying a good death, as it asserts that no person was beyond forgiveness and that anyone that was truly sorry for their sins could earn their place in heaven.

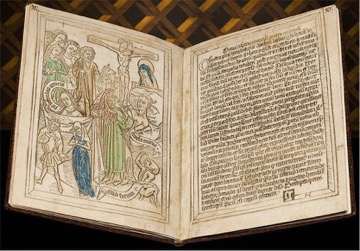

Figure 1: Ars Moriendi Blockbook

The Ars Moriendi (‘The Art of Dying’) is a fifteenth-century Latin text that instructed people on how to die a good death, ensuring them an eventual place in heaven. While this text was popular throughout Europe, this version was printed in the Netherlands c.1467–1469.

EXHIBIT 1: POST-MORTEM SENTIENCE

Carved cadaver tombs are a form of memorial sculpture that developed during the late medieval period in Western Europe. They represented the transition between life and death, depicting elite individuals at the moment of death, in an emaciated state, with their heads tipped back and their mouths open in anguish. This relates to the idea of ‘post-mortem sentience’. According to Christina Welch, in the medieval period, it was commonly believed that, although the corpse was physically dead, the soul could linger for up to a year after death. The anguish of the carved cadaver reminded the living of the physical pain experienced by those in purgatory, encouraging people to pray for those represented on the tomb to lessen their suffering. Like other forms of Memento Mori, cadaver tombs served as a reminder of the inevitability of death, as they often included dedications such as ‘I was like you and you will be like me’. Moreover, by depicting the dead in a naked and emaciated state, these memorials also visually communicated the idea that death was a social leveller, as the deceased have been stripped of all their earthly possessions and status symbols, as these were of no use to the dead.

Figure 2: The Tomb of Henry Chichele, Archbishop of Canterbury.

The first English carved cadaver memorial belonged to the Archbishop Henry Chichele and was constructed c.1425, during Chichele’s lifetime, in Canterbury Cathedral (Figure 2). Like most cadaver tombs, it is a multi-layered monument. The top depicts Chichele’s soul in its perfect form, while the bottom layer depicts a naked, emaciated corpse. This, along with the inscription that reads ‘I was a pauper born, then to primate here raised, now I am cut down and served up for worms … Whoever who may be who will pass by, I ask for your remembrance’, reminds viewers that, no matter what they achieved in life, they too will one day die.

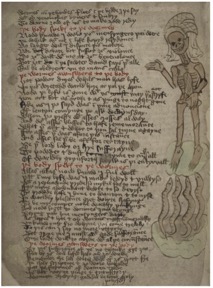

Figure 3: A Disputation between the Body and the Worms.

This Middle-English Poem (Figure 3), dating to c.1435-1440, is a literary reflection of the ideas embodied in carved cadaver tombs. It centres around a discussion about universal salvation that takes place between a dead noblewoman and the worms that are eating her corpse. The worms claim that a person must atone for their sins before dying for their soul to go to heaven, while the woman suggests that forgiveness can be granted, even after death, no matter how sinful a life someone has led. The poem does not offer a definitive answer on this topic, leaving readers to make their own judgement about the importance of living a pious life.

EXHIBIT 2: THE THREE LIVING AND THE THREE DEAD

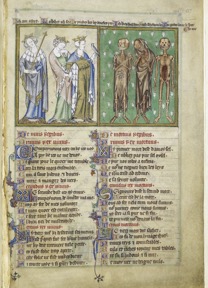

Figure 4: The De Lisle Psalter.

This Memento Mori genre is believed to have originated in thirteenth-century France. It depicts three living, usually elite men next to a mirror image of three skeletons without rank or distinction. That the three living are depicted as aristocratic individuals suggests that it was believed that there was a need for moral correction among the elite, as the corpses remind the three living that they too will die and become like them, devoid of any social status, reminding them that it is more important to live a pious life in preparation for the afterlife than it is to acquire earthly wealth or power. Although this genre originated as a criticism of aristocratic greed, its warning to live a virtuous life could be applied to any social group. Indeed, it proved to be one of the most dynamic and widely diffused depictions of death in the medieval period, appearing in both elaborate aristocratic manuscripts and on church walls where its message could be communicated to the whole local population.

One of the earliest and most well-known depictions of the Three Living and the Three Dead in English visual culture comes from the De Lisle Psalter (Figure 4), an aristocratic manuscript from the early fourteenth century. The image shows three crowned women, mirrored by three skeletons. The Three Living state: ‘I am afraid’, ‘Lo, what I see!’, and ‘Methinks these be devils three’, while the Three Dead reply: ‘I was well fair’, ‘Such shall you be’ and ‘For God’s love, beware by me’, reminding readers of their inevitable death and that they too will end up as an anonymous corpse no matter what status they achieve in life.

EXHIBIT 3: THE DANSE MACABRE

Figure 5a: Morgan Book Of Hours

Most scholars believe that the Danse Macabre evolved from the legend of the Three Living and the Three Dead, although it may have also been influenced by the folklore belief that the dead left their graves to dance at night. Like the Three Living and the Three Dead, the Danse Macabre is also believed to have originated in France, as the first known Dance of Death mural was located in the Cimetière des Innocents in Paris. The Danse Macabre featured people from all social groups, including popes, peasants, and even young children, once again communicating that death was inevitable for everyone, even if it was unexpected for some, meaning one should always be prepared for the possibility of dying and not leave it too late to atone for their sins, as this would be detrimental to their place in the afterlife. Dancers are often shown reaching for the life they are being forced to leave behind, although the cadavers show them little sympathy. Indeed, they sometimes seem as if they want to punish the dancers for their sins, perhaps as a way of communicating the unforgiving nature of death.

Figure 5b: Morgan Book Of Hours

The Morgan Danse Macabre Cycle (Figures 5a and 5b) was produced in Paris c.1430, a time when English control over the city was under serious threat due to the weakening of the Anglo-Burgundian alliance. The urban setting of the images helps to create a realistic depiction of Parisian life, as many of the figures depicted in the cycle are actively working when death comes for them. They are not passive participants in the danse, but are reluctantly pulled away by death, something they cannot avoid.

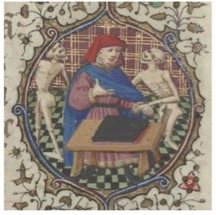

Figure 6: Holbein’s Letter A.

Hans Holbein’s Alphabet of Death (Figure 6) was designed for German woodcutter Hans Lützelburger, although it proved to be incredibly popular and soon spread throughout Europe. The Danse opens with musical cadavers in the letter ‘A’ while each subsequent letter contains a ‘direct and unambiguous confrontation’ between the living and the dead, meaning the core message of the genre – that death comes for all – could reach even the illiterate.

EXHIBIT 4: DEATH AND THE MAIDEN

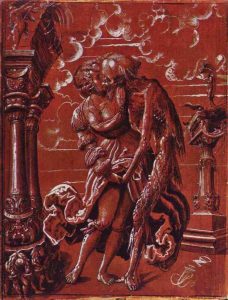

Figure 7: Deutsch’s Death and the Maiden.

Little is known about the origins of this motif, but it is believed to have developed in early sixteenth-century Germany. Unlike the older forms of memento mori, where death was usually depicted as genderless, death in this genre is almost always personified as male. The sexuality of death’s female partner is used to warn men of the damnation that results from earthly pleasures by reminding them of the closeness of death, as the explicit eroticism of Death and the Maiden imagery elicited a sexually charged response from viewers, making its message visceral as well as visual.

Niklaus Manuel Deutsch’s 1517 drawing (Figure 7) depicts death as a decomposing figure kissing a young woman meant to personify earthly pleasure. The maiden seems to be a willing participant in this act, accepting death as her lover, highlighting the complicity of women in causing men to fall victim to temptations of the flesh, resulting in their damnation.

Comments

No comments.