Working the Ocean’s White Gold: A Nutshell History of a Living Bering Strait Tradition

4 March 2025

By Michael Engelhard

Sculpting walrus tusks is an act of transformation, turning animal into art. It also is revitalization: what is dead once more becomes animated. Lastly, it is the thrill of discovery. What hides in there? asks the carver, exploring a silky arc with callused hands.

Throughout the Bering Strait region and Arctic coastal Alaska, the earth has yielded walrus ivory artifacts thousands of years old. The practice of manufacturing things of transcendent beauty from the sea’s white gold still is vigorous. In Savoonga on St. Lawrence Island (the “Walrus Capital of the World”), nearly every resident has a relative who is an ivory carver. They sell their creations to tourists or mainlanders living there, to private collectors and galleries, and to gift shops and wholesalers like Maruskiya’s of Nome, whose window on Front Street brims with finely wrought treasure like Aladdin’s cave. Inupiat from King Island, another sea-mammal hunting outpost, also market their wares through this store.

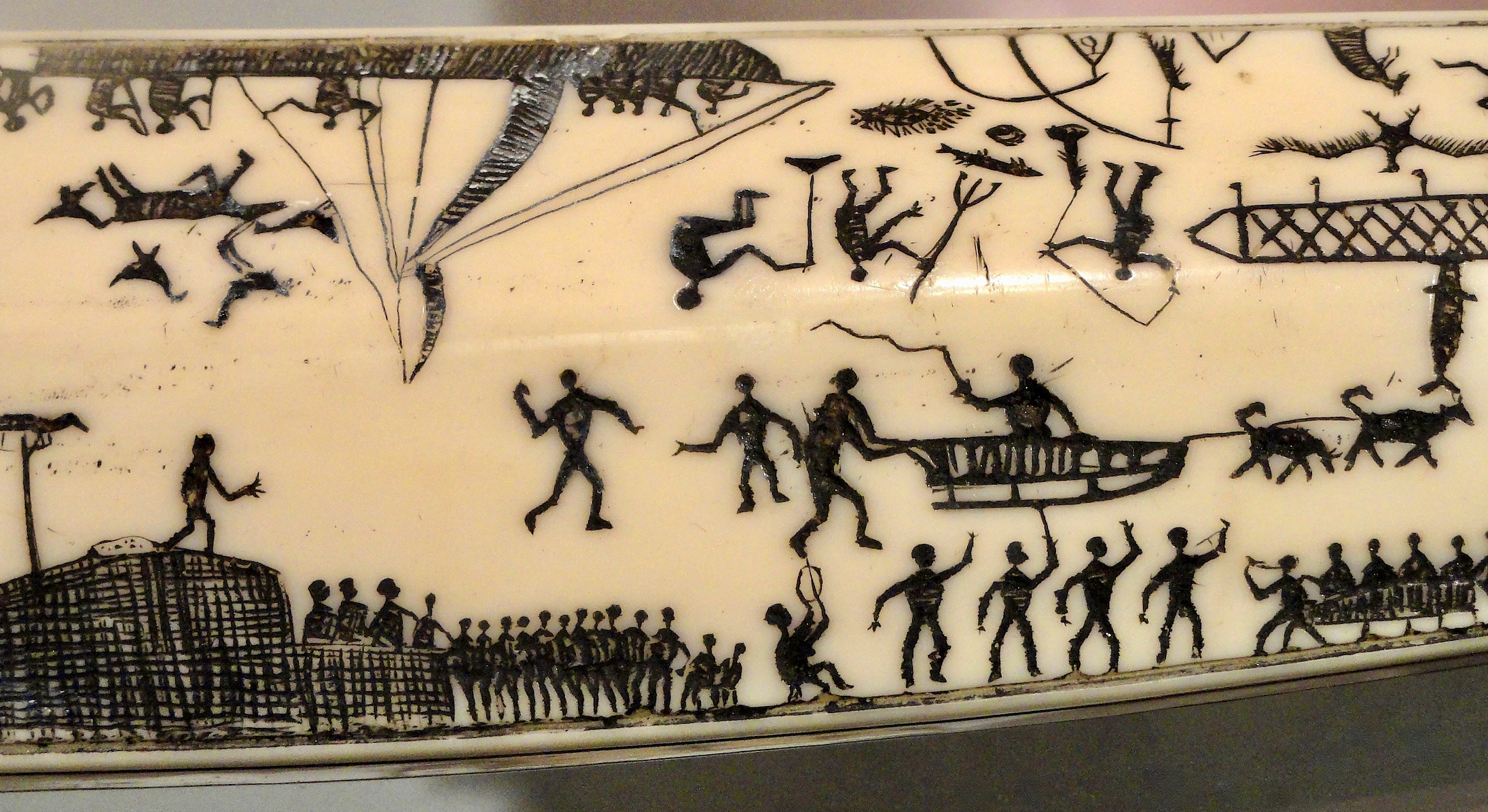

Before contact with Europeans, Eskimo people had little access to metal or wood and therefore cultivated the craft of carving bone, soapstone, and walrus ivory; more durable than wood, the curved canines were easier to process than stone. The output included ancestral images, amulets, and everyday items: needle cases, harpoons, snow goggles, fishing lures, arrow straighteners, and fancy combs. Soot or red clay rubbed into patterned grooves looked pretty, making designs pop, while adding magic and meanings.

With the influx of sailors, traders, miners, and missionaries in the late 19th century, new demands broadened Native repertoires: scenes from life, scrimshawed on entire tusks, ornamented tobacco pipes, letter openers, and sundry souvenirs and collectors’ items. Styles also changed, from semi-abstract representations of humans and animals and geometric compositions to large-scale graphics and naturalistic designs: flags, roses, sleds, boats, hunts, and cliché (and incorrect for this part of the North) igloo encampments—often copied from illustrations or photos the customer provided. Ivory carving morphed from subsistence into a cash enterprise also in Saint Michael, Teller, and on Nunivak Island. “Hundreds of Eskimo men turned out thousands of ivory cribbage boards, gavels, umbrella handles, and figurines for the local stores,” according to the anthropologist Dorothy Jean Ray.

In the 1870s, the Alaska Commercial Company at St. Michael bought walrus tusks and gave or sold them to men for engraving, since no walrus lived in the area. Elsewhere, large-scale commercial exploitation of the animal’s tusks, blubber (for lamp oil), meat, and skin (for drive belts in industrial machinery) caused Arctic populations to plummet from hundreds of thousands to 50,000 by the 1950s.

Luckily for the carvers, a second source of raw material lies underfoot: Modern Michelangelos dig fossilized walrus teeth from the normally frozen ground around prehistoric hunting camps during summer’s brief window. They chance upon them beachcombing or hunting, as rivers and wave action uncover ancient wealth. Minerals from the embedding soil tinge these gems creamy-white, bluish, or a deep, chestnut brown. An unworked fossil walrus tusk fetches about $500, depending on size. It is perfect for chiseling: soft enough to be carved with hand tools yet hard enough to be polished like stone, without need of lacquer or any other finish (fresh tusks must be seasoned before they are carved or they will crack).

Walrus are protected under the 1972 Marine Mammal Protection Act, but Alaska Natives who traditionally hunted them can continue to do so and sell byproducts—whiskers, skulls, ivory—that have been modified, upgraded into art. Alaska Natives and non-Natives may use fossilized walrus (and mammoth) ivory, though it’s illegal to take fossils from state or federal lands. In Nome, out-of-state tourists watching the Iditarod or disembarking from cruise ships like to buy locally carved ivories. Unfortunately, many don’t understand the difference between legal walrus and illegal elephant ivory. Alaska galleries complain that consequently, sales for some artists have dropped 40 percent since the ban. The buyers’ uncertainty spells hardship for carvers and their families as in this cash-poor region art pays for clothing and fuel. To make matters worse, works by fictitious “Eskimo” carvers, frequently mass-produced and from elephant tusks, infiltrate markets.

Today’s carvers have changed with the times. Instead of bow drills and files, many now prefer dental or electric tools, and Sharpies, not India ink, for tracery. Souvenirs can no longer be had for tobacco, flour, or nails. Statuettes with inlaid baleen eyes or trim, engraved with lines filled with black pigment, and set on fossilized ivory bases cost thousands of dollars apiece, as do embellished skulls with tusks in place. Regardless of trends, the creative process and artistic sensibilities remain unchanged. The carver, observer of physical and spirit realms, makes them tangible for the rest of us with vision and skill.

This essay is excerpted from No Place Like Nome: The Bering Strait Seen Through Its Most Storied City, which is available for preordering. Michael Engelhard, who lived for three years in this storyteller’s Eldorado by the sea, has a degree in cultural anthropology from the University of Alaska Fairbanks. He also is the author of the National Outdoor Book Award-winning memoir Arctic Traverse and of the cultural history Ice Bear.

- From the Floe Edge: Visualising Sea Ice in Kinngait, Nunavut

- Bridging Knowledge and Action: A Polish-Norwegian Perspective on Arctic Science-Policy Collaboration

- Unpacking the Motivation Behind Wintering at Polar Stations

- Working the Ocean’s White Gold: A Nutshell History of a Living Bering Strait Tradition

- Political Participation in the Arctic: Who is heard, when, and how?