The ’Greenland card’ – Arctic Colonialism in the Cold War Era

7 January 2020By Iben Bjørnsson

The Second World War had significant consequences for Greenland. Greenland was cut off from her colonial metropole and, for the first time in several hundred years, the strict monopoly that Denmark had upheld was broken. One of new players entering Greenland in this power vacuum was the USA, for which the war meant an increased strategic interest in Greenland.

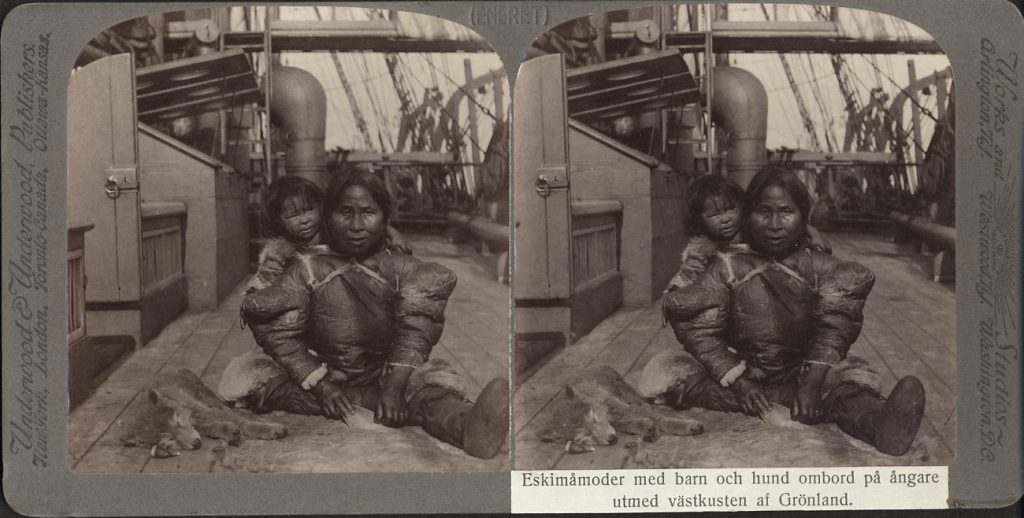

This interest became no less when war turned to Cold War. During the war, the US had built 14 bases or stations in Greenland. One of them, the weather station Bluie West 6, was built in 1943 by the settlement of Uummannaq on the west coast. Uummannaq was home to a small tribe of hunters, the Inughuit, who had settled here for the simple reason that these were fertile hunting grounds. In 1909 came a Danish missionary station and in 1910, Danish Arctic explorers Knud Rasmussen and Peter Freuchen set up a trading station here and named it Thule. Being already occupied by westerners was a contributing factor to the American choosing the site for their weather station.

As war turned to Cold War, the American strategic interest in the area only became bigger. The reason for this was, as it often is, one of simple geography. The shortest flying route from Washington to Moscow is over Greenland. If someone in Washington wanted to attack Moscow by air, or be warned that Moscow was about to launch an attack of its own, Greenland was considered indispensable. Denmark, being in somewhat bad standing internationally for cooperating with the German occupation power, was not in a position to throw the Americans out of Greenland. They wanted to stay, and they wanted to stay at Thule, where a small air strip had been built in 1946. When Denmark and the US joined forces in NATO in 1949, it was only a matter of time, before the arrangement would be formalized. This happened in 1951, with an agreement granting the US the right to build an air base at Thule, which would function both as a steppingstone and a warning station. And thus, building began.

This created problems for the Inughuit. The noisy building machines and plane traffic scared off the game. Moreover, large stretches of the hunting plains were sealed off and fenced in. But perhaps most worried, and worrisome, was the Danish colonial administration who thought that the proximity of Americans risked being at odds with the Danish “protection policy”, according to which indigenous peoples of Greenland should be shut off from the modern world and its “damaging” influences.

The Danish colonial authorities decided to move the Inughuit. On 25 May 1953, Danish officials came to Uummannaq and told the inhabitants that they had four days to pile all their belongings on a sledge and head north. On 31 May Uummannaq was empty. The new location, Qaanaaq was 130 kilometres north.

Obviously, the experience was traumatic for the Inughuit; and why the rush? Well. On June 5, a new Danish constitution was to take effect. One of the biggest changes was that it now also applied to Greenland.

The Danish rules for expropriation of land (including reparations) are laid down in the constitution and from June 5, that would also cover Thule. It has never been proven that the Danish government purposely moved the population before June 5 to avoid the new constitution. But in Greenlandic circles the timing seems a little too obvious to be a coincidence.

But why did the Americans have to have a base right there? The answer holds a gloomy irony. The people were there because the food was there. Knud Rasmussen built his colony by the settlement, because the people were there. The weather station and airstrip was established because the colony was there. And the base was built there because the weather station and the air strip was there.”

Aside from being incredibly traumatic, the forced removal held another problem: conditions for hunting in the new location was not nearly as favourable as it had been at Uummannaq. But the removal, with all the problems attached to it, was not spoken of publicly for many years. Uummannaq was torched to ensure that no one came back.

Following some publicity in the mid to late 1980’es the Danish state formed a commission, which investigated the matter for seven years and in 1994 came to the conclusion that the state had done nothing wrong.” Upon this, the Inughuit sued the Danish state. In 1999 the Danish High Court ruled that they had in fact been forcibly removed. The win even led to an official apology by the prime minister – the only apology ever issued by Denmark to anyone in its former colonies. The win also came with a compensation to the forcibly removed Inughuit, albeit a very small one – just 15.000 Danish kroner, the equivalent of 2.000 euros. And it didn’t solve the real problem: that Qaanaaq is not as rich a hunting ground as Uummannaq, making it that mush harder for the Inughuit to sustain themselves. Any attempts to have their old land back, however, has been futile: The High Court ruled, that even though the Inughuit had been forced off their land, the land was not covered by the rules of expropriation under the Danish Constitution at the time. Remember? The new constitution also covering Greenland didn’t take effect until a week after the forced removal. Hence, even if the people had been treated wrongly, the court ruled that taking the land itself was legal.

But even if they were to return, the air base it still there – and with it, new problems such as pollutions from its installation and garbage dumps. An aspect of the discussion has been whether Denmark gave the US free reigns in Greenland as a trade-off for not always living up to the military goals set by NATO. It is referred to as “the Greenland card” and is a contested term among historians and politicians. And with Donald Trump’s recent suggestion that the US buy Greenland from Denmark, there are no signs that US (or Russian) strategic interest is on the wane. On the contrary, we need to brace ourselves for an increased strategic interest in the northernmost areas. What we can only hope for is that this time around, with political frameworks such as the Arctic Council, the Indigenous Peoples’ Secretariat and the Greenland Self-rule Government, the voice of the people actually living there will be heard.

Iben Bjørnsson holds a Ph.D. in History from the University of Copenhagen and specialises in contemporary history and politics with an emphasis on the Nordic countries. She is a curator at the Stevnsfort Cold War Museum in Denmark.

- From the Floe Edge: Visualising Sea Ice in Kinngait, Nunavut

- Bridging Knowledge and Action: A Polish-Norwegian Perspective on Arctic Science-Policy Collaboration

- Unpacking the Motivation Behind Wintering at Polar Stations

- Working the Ocean’s White Gold: A Nutshell History of a Living Bering Strait Tradition

- Political Participation in the Arctic: Who is heard, when, and how?